Software Engineering at Google

Table of contents

1: What is Software Engineering?

We see three critical differences between programming and software engineering: time, scale, and the trade-offs at play

- need to ask yourself: “What is the expected life span1 of your code?”

- Your project is sustainable if, for the expected life span of your software, you are capable of reacting to whatever valuable change comes along, for either technical or business reasons.

- When you are fundamentally incapable of reacting to a change in underlying technology or product direction, you’re placing a high-risk bet on the hope that such a change never becomes critical.

- Somewhere along the line between a one-off program and a project that lasts for decades, a transition happens: a project must begin to react to changing externalities

- must be aware of difference between “happens to work” and “is maintainable”

hyrum’s law: With a sufficient number of users of an API, it does not matter what you promise in the contract: all observable behaviors of your system will be depended on by somebody.

- cannot assume perfect adherence to published contracts or best practices

We’ve taken to saying, “It’s programming if ‘clever’ is a compliment, but it’s software engineering if ‘clever’ is an accusation.”

Change is not inherently good. We shouldn’t change just for the sake of change. But we do need to be capable of change

churn rule: policy at google that says infrastructure teams must do the work to move their internal users to new versions themselves or do the update in place, in backward-compatible fashion

Beyonce rule: policy at google: “If a product experiences outages or other problems as a result of infrastructure changes, but the issue wasn’t surfaced by tests in our Continuous Integration (CI) system, it is not the fault of the infrastructure change.”

Knowledge is viral, experts are carriers, and there’s a lot to be said for the value of clearing away the common stumbling blocks for your engineers.

- the more you change your infrastructure, the easier it is to do so

- factors that affect the flexibility of a codebase: expertise, stability, conformity, familiarity, policy

- shift left - as with other shift left movements, the earlier you catch bugs, the easier it is to resolve them

types of costs

- Financial costs (e.g., money)

- Resource costs (e.g., CPU time)

- Personnel costs (e.g., engineering effort)

- Transaction costs (e.g., - what does it cost to take action?)- Opportunity costs (e.g., what does it cost to not take action?)

-

Societal costs (e.g., what impact will this choice have on society at large?)

- should rely on data, but when there is no data, you have evidence, precedent, and argument

Jevons Paradox - consumption of a resource may increase as a response to greater efficiency in use

Chapter Summary

- “Software engineering” differs from “programming” in dimensionality: programming is about producing code. Software engineering extends that to include the maintenance of that code for its useful life span.

- There is a factor of at least 100,000 times between the life spans of short-lived code and long-lived code. It is silly to assume that the same best practices apply universally on both ends of that spectrum.

- Software is sustainable when, for the expected life span of the code, we are capable of responding to changes in dependencies, technology, or product requirements. We may choose to not change things, but we need to be capable.

- Hyrum’s Law: with a sufficient number of users of an API, it does not matter what you promise in the contract: all observable behaviors of your system will be depended on by somebody.

- Every task your organization has to do repeatedly should be scalable (linear or better) in terms of human input. Policies are a wonderful tool for making process scalable.

- Process inefficiencies and other software-development tasks tend to scale up slowly. Be careful about boiled-frog problems.

- Expertise pays off particularly well when combined with economies of scale.

- “Because I said so” is a terrible reason to do things.

- Being data driven is a good start, but in reality, most decisions are based on a mix of data, assumption, precedent, and argument. It’s best when objective data makes up the majority of those inputs, but it can rarely be all of them.

- Being data driven over time implies the need to change directions when the data changes (or when assumptions are dispelled). Mistakes or revised plans are inevitable.

2: How to Work Well on Teams

- software dev is a team endeavor

- The Genius Myth is the tendency that we as humans need to ascribe the success of a team to a single person/leader

- need to avoid, since best creations are mostly group activities

-

the bus factor - the number of people that need to get hit by a bus before your project is completely doomed.

- Ensuring that there is at least good documentation in addition to a primary and a secondary owner for each area of responsibility helps future-proof your project’s success and increases your project’s bus factor.

- key to software delivery - get feedback as early as possible, test as early as possible, think about security and the production environments as early as possible

- working alone is inherently riskier than working with others

Three Pillars of Social Interaction

Pillar 1: Humility

- You are not the center of the universe (nor is your code!). You’re neither omniscient nor infallible. You’re open to self-improvement.

Pillar 2: Respect

- You genuinely care about others you work with. You treat them kindly and appreciate their abilities and accomplishments.

Pillar 3: Trust

- You believe others are competent and will do the right thing, and you’re OK with letting them drive when appropriate.

It’s not about tricking or manipulating people; it’s about creating relationships to get things done.

The trick is to make sure you (and those around you) understand the difference between a constructive criticism of someone’s creative output and a flat-out assault against someone’s character.

if you’re not failing now and then, you’re not being innovative enough or taking enough risks. Failure is viewed as a golden opportunity to learn and improve for the next go-around

- blameless post-mortems are really important to learning – always need to contain an explanation of what was learned and what is going to change as a result of the learning experience

The more open you are to influence, the more you are able to influence; the more vulnerable you are, the stronger you appear.

Being “Googley”

rubric of behaviors for what is “googley”:

Thrives in ambiguity

- Can deal with conflicting messages or directions, build consensus, and make progress against a problem, even when the environment is constantly shifting.

Values feedback

- Has humility to both receive and give feedback gracefully and understands how valuable feedback is for personal (and team) development.

Challenges status quo

- Is able to set ambitious goals and pursue them even when there might be resistance or inertia from others.

Puts the user first

- Has empathy and respect for users of Google’s products and pursues actions that are in their best interests.

Cares about the team

- Has empathy and respect for coworkers and actively works to help them without being asked, improving team cohesion.

Does the right thing

- Has a strong sense of ethics about everything they do; willing to make difficult or inconvenient decisions to protect the integrity of the team and product.

Chapter Summary

- Be aware of the trade-offs of working in isolation.

- Acknowledge the amount of time that you and your team spend communicating and in interpersonal conflict. A small investment in understanding personalities and working styles of yourself and others can go a long way toward improving productivity.

- If you want to work effectively with a team or a large organization, be aware of your preferred working style and that of others.

3: Knowledge Sharing

12: Unit Testing

After preventing bugs, the most important purpose of a test is to improve engineers’ productivity.

properties of unit tests

- tend to be small, which makes them fast and deterministic and can be run often

- easy to write at the same time as the code they are testing

- promote high levels of test coverage because they are quick and easy to write

- easy to understand what is wrong with them when they fail

-

can serve as documentation and examples

- shoot for a mix of 80% unit tests, 20% broader-scoped tests

- when writing tests, you want maintainability, and want to avoid:

- brittle: breaking in response to harmless or unrelated changes

- unclear: difficult to determine what is wrong and how to fix it

- strive for unchanging tests – after a test is written, it never needs to change unless the requirements of the system change

four kinds of change

- pure refactorings – shouldn’t require unit test changes because you shouldn’t be changing the API, just implementation underneath

- new features – should just be adding new unit tests, not changing what already exists

- bug fixes – an uncaught bug means a test didn’t exist, so additive

- behavior changes – only case where you need to update unit tests

write tests that invoke the system being tested in the same way its users would; that is, make calls against its public API rather than its implementation details.

state and interaction testing

- state testing: you observe the system itself to see what it looks like after invoking with it

- interaction testing: check that the system took an expected sequence of actions on its collaborators in response to invoking it

- you should prefer state testing because we generally don’t care how a system arrives at state, just that it is in a particular state

Two high-level properties that help tests achieve clarity are completeness and conciseness. A test is complete when its body contains all of the information a reader needs in order to understand how it arrives at its result. A test is concise when it contains no other distracting or irrelevant information.

behavior testing

- rather than write tests for each method, write tests for each behavior

- a behavior is a guarantee that a system makes about how it will respond to a series of inputs while in a particular state

- behaviors can often be expressed via “given”, “when”, and “then”

-

name and structure tests around the behaviors being tested

- don’t put logic in tests

- write clear failure messages

Instead of being completely DRY, test code should often strive to be DAMP—that is, to promote “Descriptive And Meaningful Phrases.” A little bit of duplication is OK in tests so long as that duplication makes the test simpler and clearer.

TL;DR

- Strive for unchanging tests.

- Test via public APIs.

- Test state, not interactions.

- Make your tests complete and concise.

- Test behaviors, not methods.

- Structure tests to emphasize behaviors.

- Name tests after the behavior being tested.

- Don’t put logic in tests.

- Write clear failure messages.

- Follow DAMP over DRY when sharing code for tests.

13: Test Doubles

-

test double - an object or function that can stand in for a real implementation

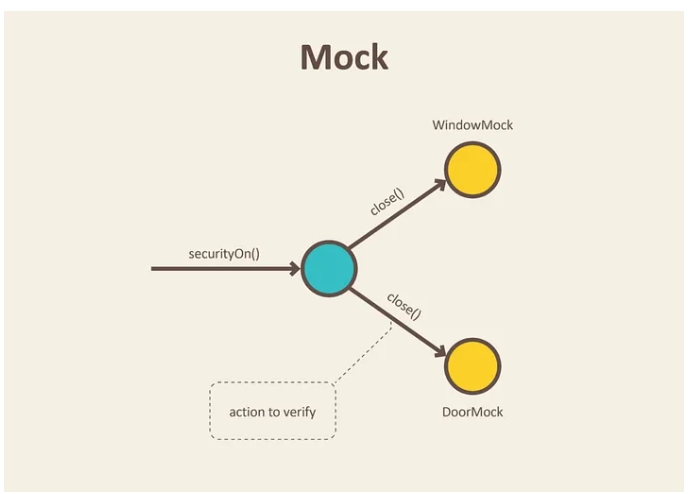

- sometimes referred to as “mocking”, but often mocking refers to more specific type of test double

- key concepts:

- testability: it should be possible for tests to swap out real implementations with test doubles

- applicability: there is a tradeoff between engineer velocity introduced by applying test doubles, and over-usage resulting in brittle, complex, ineffective tests

- fidelity: how closely a behavior a test double tests to the actual implementation

- Code is said to be testable if it is written in a way that makes it possible to write unit tests for the code. A seam is a way to make code testable by allowing for the use of test doubles—it makes it possible to use different dependencies for the system under test rather than the dependencies used in a production environment.

- Dependency injection is a common technique for introducing seams. In short, when a class utilizes dependency injection, any classes it needs to use (i.e., the class’s dependencies) are passed to it rather than instantiated directly, making it possible for these dependencies to be substituted in tests.

- a mock is a test double whose behavior is specified inline in a test

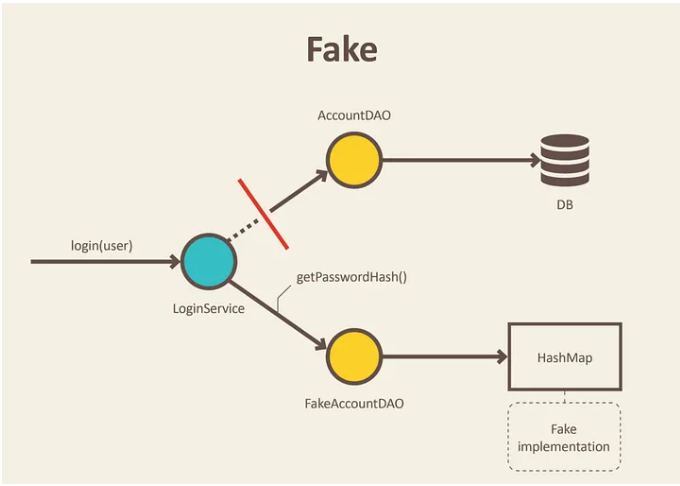

- a fake is a lightweight implementation of an API that behaves similar to the real implementation but isn’t suitable for production

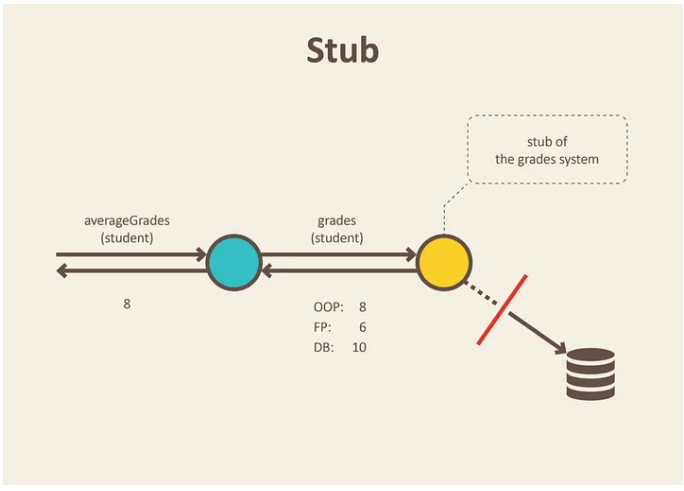

- a stub is the process of giving behavior to a function that otherwise has no behavior on its own

- interaction testing: a way to validate how a function is called without actually calling impl. of the function

- classical testing: preferring real impl. in tests, and generally a more robust and diagnostic way to test

- a real implementation is preferred if it is fast, deterministic, and has simple dependencies

- a test is deterministic if, for a given version of the system under test, running the test always results in the same outcome

- hermetic: self-contained; dependencies on external services outside the control of the test means it might not be deterministic

TL;DR

- A real implementation should be preferred over a test double.

- A fake is often the ideal solution if a real implementation can’t be used in a test.

- Overuse of stubbing leads to tests that are unclear and brittle.

- Interaction testing should be avoided when possible: it leads to tests that are brittle because it exposes implementation details of the system under test.