Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces

Remzi Arpaci-Dusseau, Andrea Arpaci-Dusseau. 2015

Key Links

- https://pages.cs.wisc.edu/~remzi/OSTEP/Homework/homework.html

- https://pages.cs.wisc.edu/~remzi/OSTEP/

- https://github.com/remzi-arpacidusseau/ostep-code

Table of contents

- 4 - The Process

- 5 - Process API

- 6 - Limited Direct Execution

- 7 - Scheduling

- 8 - Multi-Level Feedback Queue

- 9 - Scheduling - Proportional Share

- 10 - Multiprocessor Scheduling (Advanced)

- 13 - The Abstraction: Address Spaces

- 14 - Memory API

- 15 - Mechanism: Address Translation

- 16 - Segmentation

- 17 - Free Space Management

- 18 - Paging

- 18 - Translation-Lookaside Buffers

- 20 - Paging: Smaller Tables

- 21 - Beyond Physical Memory: Mechanisms

- 22 - Beyond Physical Memory: Policies

- 23 - Complete Virtual Memory Systems

4 - The Process

- a process is a running program

- in order to run multiple processes at once, the OS creates the illusion of multiple CPUs by virtualizing the CPU

- achieves this by:

- mechanisms - low level methods or protocols that implement a needed piece of functionality

- policies - algorithms for making some kind of decision within the OS

- state of a process can be described by:

- the contents of memory in its address space,

- the contents of CPU registers (including the program counter and stack pointer, among others), and

- information about I/O (such as open files which can be read or written)

Sharing

- time sharing - allowing one entity to use a resource for a little while then context switching to allow another entity to use the resource (e.g., CPU, network link)

-

space sharing - a resource is divided in space among users (e.g., disk space)

- understanding process is understanding machine state

- memory - where programs instructions live via address space

- registers - things like program counter/instruction pointer (what the next instruction is)

- I/O info

Process API

- create - method to create new processes

- destroy - method to destroy running processes

- wait - method to pause a running process

- misc. control - other special methods, like suspend or resume

- status - get status info about process

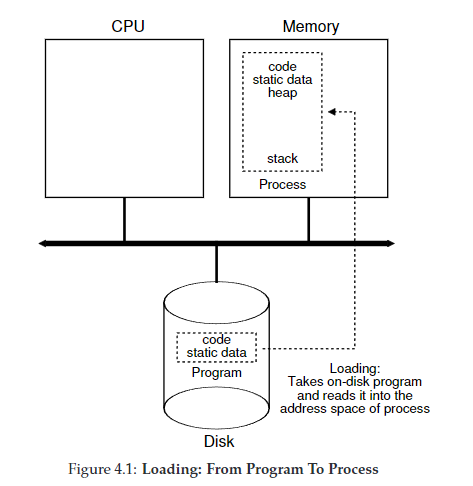

programs can either be loaded

- eagerly: all at once before running the program

- lazily: loading pieces of code or data only as they are needed during program execution

how are programs turned into processes?

- code and any static data loaded into memory

- this used to be done eagerly (load the whole program into memory), now it is typically done lazily (load only needed modules)

- stack is provisioned

- in C programs, stack is used for variables, function parameters, etc

- program might also allocate memory for program’s heap

- in C programs, memory for heap gets provisioned with

malloc()and freed withfree()

- in C programs, memory for heap gets provisioned with

- OS will do other initialization tasks such as setting up file descriptors (standard out, standard in, standard err)

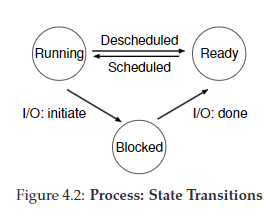

Process States

RUNNING - the process is using the CPU right now READY - the process could be using the CPU right now but (alas) some other process is BLOCKED - the process is waiting on I/O (e.g., it issued a request to a disk) DONE - the process is finished executing ZOMBIE - the process has completed executing but there is still an entry in the process table

- there are potentially other process states, for example

enum proc_state { UNUSED, EMBRYO, SLEEPING, RUNNABLE, RUNNING, ZOMBIE };

Data Structures

- process list - aka task list, keeps track of all running programs

- process control block - aka process descriptor, individual structure that stores information about each process, an entry in the process list

5 - Process API

- process identifier - aka PID, used to identify a process

- the separation of fork and exec enables features like input/output redirection, pipes, and other cool features

the fork system call

- used to create a new process

- creates almost an exact copy of the parent process as a child process, key difference is PID

- not deterministic, as the parent or child might finish executing first

- if you want to implement determinism, you implement a call to wait for the parent

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

int main(int argc, char*argv[]) {

printf("hello world (pid:%d)\n", (int) getpid());

int rc = fork();

if (rc < 0) { // fork failed; exit

fprintf(stderr, "fork failed\n");

exit(1);

} else if (rc == 0) { // child (new process)

printf("hello, I am child (pid:%d)\n", (int) getpid());

} else { // parent goes down this path (main)

int rc_wait = wait(NULL);

printf("hello, I am parent of %d (rc_wait:%d) (pid:%d)\n",

rc, rc_wait, (int) getpid());

}

return 0;

}

the wait system call

- allows a parent to wait for its child to complete execution.

- a way to introduce determinism into parent/child execution

the exec system call

- useful when you want to run a program that is different from the calling program

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

int main(int argc, char*argv[]) {

int rc = fork();

if (rc < 0) {

// fork failed

fprintf(stderr, "fork failed\n");

exit(1);

} else if (rc == 0) {

// child: redirect standard output to a file

close(STDOUT_FILENO);

open("./p4.output", O_CREAT|O_WRONLY|O_TRUNC, S_IRWXU);

// now exec "wc"...

char*myargs[3];

myargs[0] = strdup("wc"); // program: wc (word count)

myargs[1] = strdup("p4.c"); // arg: file to count

myargs[2] = NULL; // mark end of array

execvp(myargs[0], myargs); // runs word count

} else {

// parent goes down this path (main)

int rc_wait = wait(NULL);

}

return 0;

}

Process Control

- available in the form of signals which can cause jobs to stop, continue, or terminate

- which processes can be controlled by whom is encapsulated in the idea of a user – a user can only control their own processes

- a superuser can control all processes, as well as other privileged actions

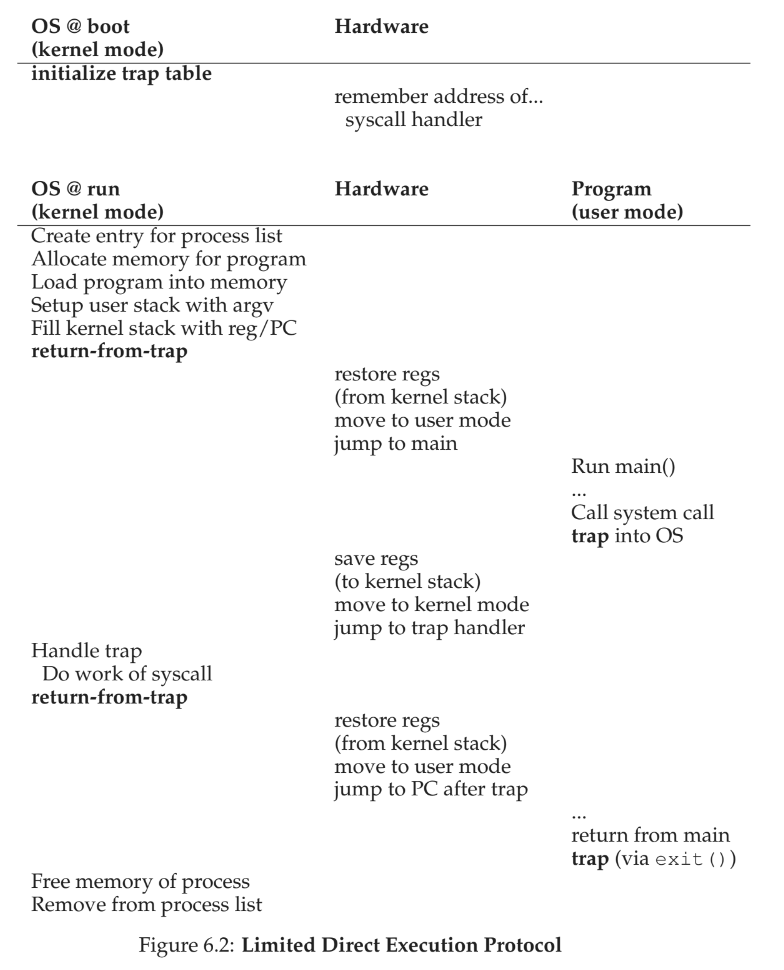

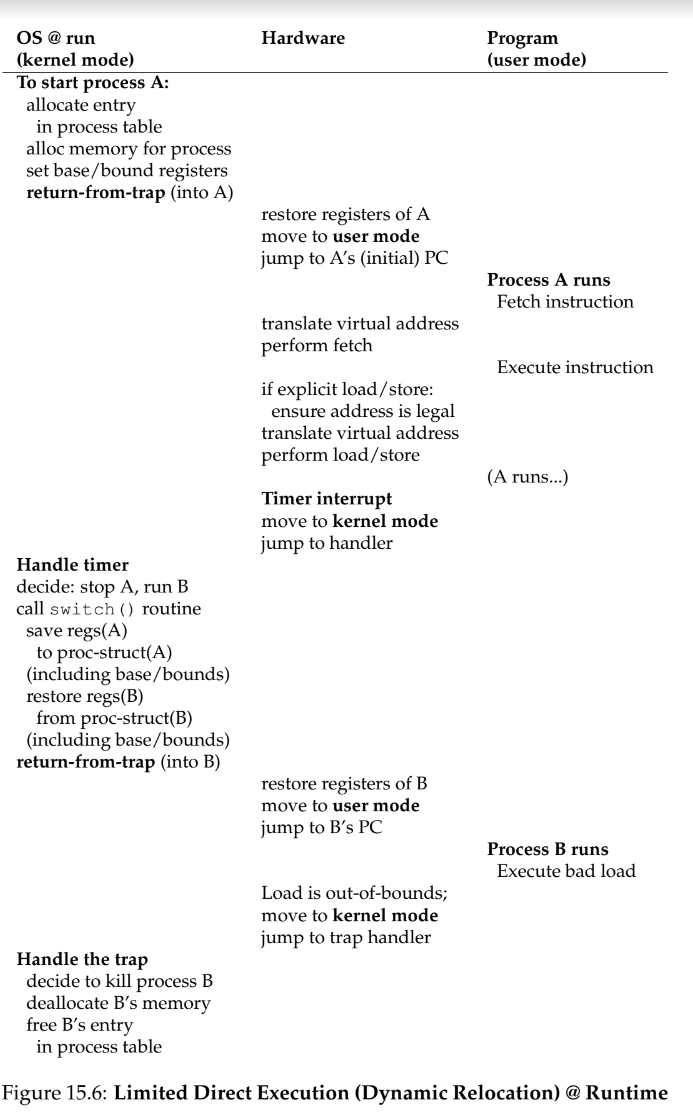

6 - Limited Direct Execution

- when virtualizing a CPU via time sharing, need to be concerned with

- performance - how to implement virtualization without excessive overhead

- control - how can run processes while retaining control over CPU

scheduler - part of the OS that decides what processes run on the CPU and when

limited direct execution - run a program directly on the CPU, with limits on how long a process can run on the CPU

when the OS wants to start a program, it

- creates a process entry in the process list

- allocates memory

- loads the program code into memory

- locates the entry point

- jumps to the entry point

- starts running

Processor Modes

- user mode - code run here is restricted in what it can do

- kernel mode - used for privileged operations like I/O or restricted instructions, and is the mode the OS runs in

system calls - allow the kernel to carefully expose certain key pieces of functionality to user programs - accessing the file system - creating and destroying processes - communicating with other processes - allocating more memory

- a trap saves caller’s registers so it can return correctly by pushing data to the kernel stack; a return from trap operation will pop these values off the stack

- trap instruction - program must execute this in order execute a system call; instruction jumps into kernel and raises the privilege to kernel mode

- trap table - a table of what happens on exceptional events like keyboard interrupts, and is set up at boot time

Switching Between Processes

- cooperative - OS trusts processes to give up control to the CPU periodically

- non-cooperative - OS implements a mechanism like a timer interrupt to take back control of CPU

context switch - low-level technique to switch from one running process to another lmbench - useful to for measuring how long things take on linux

7 - Scheduling

- scheduling is higher level policy for when to apply lower level mechanism (e.g., context switching) when virtualizing resources

- in order to compare different scheduling policies, need metrics to compare

Key Metrics

turnaround time

- time in which a job completes minus the time a job arrives

- $ T_{turnaround} = T_{completion} - T_{arrival} $

fairness

- the equality with which jobs are treated

- one example is Jain’s Fairness Index

- often at odds with performance, as most fair way to run jobs isn’t often the most performant

response time

- time when a job arrives to when it’s first scheduled

- optimizations for turnaround time might not be helpful for response time

- $ T_{response} = T_{firstrun} - T_{arrival} $

overlap

- when dealing with I/O (or any blocking task), it is good to kick off the blocking task then switch, or to overlap executions

First In, First Out (FIFO)

- simplest algo for scheduling – job that arrives is first to be processed

- suffers from convoy effect – large, expensive job blocks small, fast jobs

- normally only works when all jobs run in same amount of time

Shortest Job First (SJF)

- jobs are organized based on job length at arrival

- optimal if all jobs arrive at the same time, but bad for response time

- if not all jobs arrive at same time, you need to add preemption (like an interrupt for new arrivals), called Shortest Time-to-Completion First (STCF)

- most modern schedulers are preemptive

Shortest Time-to-Completion First (STCF)

- adds preemption to shortest job first scheduling

- any time a new job enters the system, the scheduler determines which job has least time left and schedules that one

Round Robin

- aka time slicing

- instead of running job to completion, jobs are run for a time slice (aka scheduling quantum)

- need to amortize cost (spread cost out over long term) of context switching, so you don’t want to switch context too often or wait too long so as to remove all benefits of round robin algo

- round robin is more fair and like any policy that is fair will perform more poorly on turnaround time – can run shorter jobs to completion if you are willing to be unfair, which might affect response time

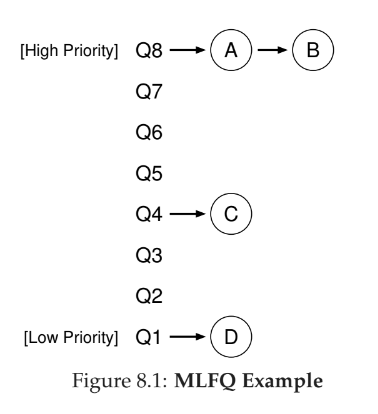

8 - Multi-Level Feedback Queue

- for most jobs, we won’t know length of jobs, so

- how do we optimize for turnaround time, and

- how do we make a system feel responsive for interactive users?

- multi-level feedback queue has multiple levels of queues, and uses feedback to determine priority of given job

- instead of demanding a priori knowledge of the nature of a job, it observes the execution of a job and prioritizes it accordingly

- manages to achieve the best of both worlds: it can deliver excellent overall performance (similar to SJF/STCF) for short-running interactive jobs, and is fair and makes progress for long-running CPU-intensive workloads

- can be difficult to parameterize: how many queues should there be, how big should the time slice be

- many systems, including BSD UNIX derivatives, Solaris, and Windows NT and subsequent Windows operating systems use a form of MLFQ as their base scheduler

- some schedulers allow you to give advice to help set priority (can be used or ignored) - e.g., linux tool

nice -

other schedulers use a decay-usage algorithm to adjust priorities (instead of a table or exact rules below)

- two problems with MLFQ

- process starvation: interactive jobs will take all the CPU time from non-interactive processes

- gaming the scheduler - a process tricking the scheduler into giving more time to the process

- a process might change its behavior, increasing in interactivity but not treated as such

priority boosts helps with process starvation by periodically bumping up the priority of jobs running in lower queues voodoo constants - constants that require some sort of black magic to set correctly

general rules outlined:

- Rule 1: If Priority(A) > Priority(B), A runs (B doesn’t).

- Rule 2: If Priority(A) == Priority(B), A & B run in round-robin fashion using the time slice (quantum length) of the given queue.

- Rule 3: When a job enters the system, it is placed at the highest priority (the topmost queue).

- Rule 4: Once a job uses up its time allotment at a given level (regardless of how many times it has given up the CPU), its priority is reduced (i.e., it moves down one queue).

- Rule 5: After some time periodS, move all the jobs in the system to the topmost queue.

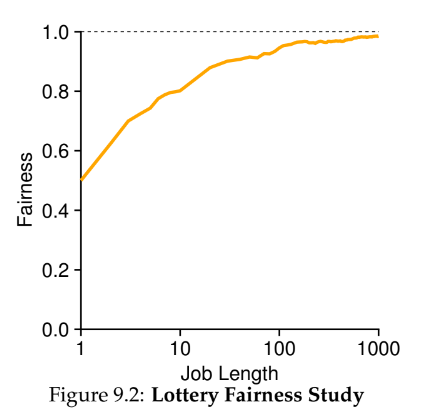

9 - Scheduling - Proportional Share

proportional share (fair-share) scheduling - instead of optimizing turnaround time, a scheduler might guarantee that each job obtain a certain percentage of CPU time

lottery scheduling

- a non-deterministic, probabilistic fair share scheduling algorithm

- every so often, hold a lottery to determine which process runs next

- tickets - represent the share of a resource that a process should receive

ways to manipulate tickets

- ticket transfer - allows a user with a set of tickets to allocate tickets among their own jobs in whatever currency they want, then those tickets are converted to global currency

- ticket transfer - a process can temporarily hand off its tickets to another process

- ticket inflation - a process can temporarily raise of lower the number of tickets it owns

lottery scheduling uses randomness, which 1. often avoids strange corner-cases 2. is lightweight, requiring little state to manage 3. can be quite fast, as long as number generation is quick

- when job length isn’t very long, lottery isn’t very fair

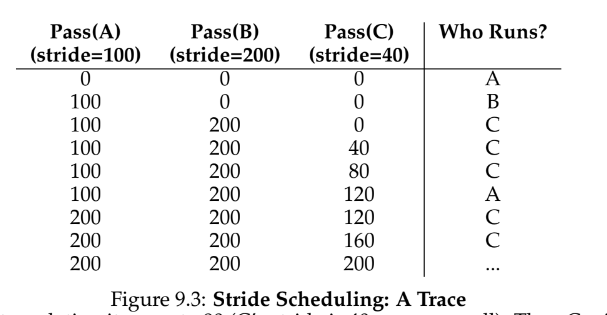

stride scheduling

- a deterministic fair share scheduling algorithm

- each process has a stride value which determines how long they run; as they run, their pass value is incremented to track global progress

- biggest drawback is that there is global state per process to manage; how do you handle new jobs that enter the system – can’t set the pass to 0 or it will monopolize CPU

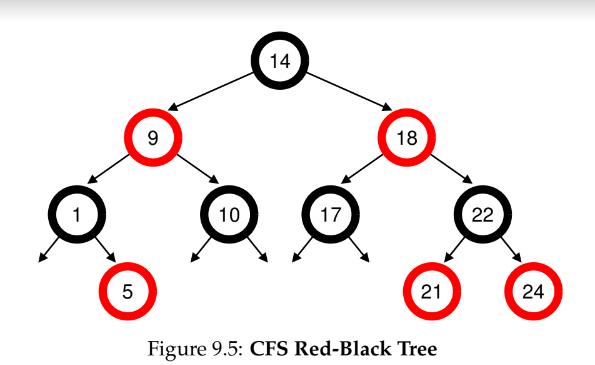

linux’s completely fair scheduler (CFS)

- scheduling uses about 5% of overall datacenter CPU time

- virtual runtime (vruntime) simple counting-based technique to divide CPU time

- each processes vruntime increases at the same rate in proportion to real time, and the scheduler will pick the process with the lowest vruntime to run next

CFS parameters

- sched_latency - determines how long a process should run before considering a switch; typical value is 48 (ms)

- min_granularity - CFS will never set the time slice of a process to less than this value; typical value is 6 (ms)

- niceness - a way to weight jobs and give priority – positive values imply lower priority

red-black trees

- CFS uses red-black trees (a balanced binary tree) to identify which job to run next

- this is logarithmic (not linear)

- only contains running jobs

10 - Multiprocessor Scheduling (Advanced)

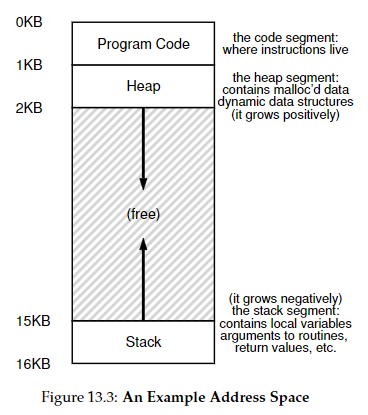

13 - The Abstraction: Address Spaces

- in the early days, machines didn’t provide a memory abstraction – one process ran at a time and used all the memory

- soon, people began to share machines thus beginning multiprogramming, where multiple processes were ready to run at any time and the OS would switch between them

- later, many people wanted to time share machines

Address Space

- an easy to use abstraction of physical memory

- the address space of a program contains all of the memory state of a running program

- stack - stores where a process is in its function call chain, local variables, and for parameters and return values to and from routines

-

heap - used for dynamically-allocated, user-managed memory (e.g.,

malloc()ornew) - stack and heap are placed at opposite ends of the address space to allow for negative and positive growth, although this is just a convention

- virtual addresses - in virtualizing the memory, a process never has a physical address, just the virtual - every address you see is virtual

Goals of the Address Space

- transparency - OS should implement virtual memory in a way that is invisible to the running program

- efficiency - OS should make the virtualization efficient in time (not making programs run much more slowly) and space (not using too much memory for structures needed to support virtualization)

- protection - OS should make sure to protect processes from one another as well as the OS – only a process should be allowed to change what it has stored in memory; important to delivery concept of isolation

14 - Memory API

Types of Memory

stack

- allocations and deallocations of stack memory are handled implicitly by the compiler

- sometimes called automatic memory for this reason

- when you return from function, the compiler deallocates this memory, so if you need data to survive the invocation of a function, don’t leave it on the stack

1

2

3

4

void func() {

int x; // declares an integer on the stack

...

}

heap

- more long-lived memory

- allocations and deallocations are handled explicitly by the programmer

1

2

3

4

void func() {

int *x = (int *) malloc(sizeof(int));

...

}

malloc()

- you pass the function a size of some room on the heap, it either succeeds and gives you a pointer to the newly-allocated space or fails and returns

NULL - pass in

size_twhich describes how many bytes you need -

NULLin C is just a macro for 0 - need to include header file

stdlib.h

double *d = (double *) malloc(sizeof(double));

- using

sizeof()is a compile-time operator and not a run-time function and is considered best practice because size of various primitives change on a per-system basis (most systemsintis 4 bytes anddoubleis 8, but not all) - for strings, use

malloc(strlen(s) + 1), the + 1 for an end-of-string character

free()

- takes one argument, a pointer returned by malloc

- size of allocated region is tracked by the memory-allocation library itself

Common Memory Errors

- many new languages are garbage collected, meaning there is a process to reclaim/free memory that is no longer in use – this is an example of automatic memory management

- segmentation fault - an error raised when you manage memory wrong

- forgetting to allocate memory - if you don’t allocate, you’ll run into a segfault and the process will die, even if the program compiled correctly

- not allocating enough memory - often called a buffer overflow; sometimes this won’t break a program but will cause some data to be unexpectedly overwritten

- forgetting to initialize allocated memory - this will cause an uninitialized read where a program will read some unknown data from the heap

- forgetting to free memory - also known as a memory leak, and affects GC languages too

- freeing memory before you are done with it - aka a dangling pointer and can cause overwritten memory or a program crash

- freeing memory repeatedly - aka a double free and the effects are undefined but often results in crashes

-

calling free() incorrectly - aka an invalid free and occurs when you pass free an unexpected value

- purify and valgrind are good tools for finding memory-related problems

-

break - the location of the end of the heap for a program and is changed via the system call

sbrkorbrk, but should never be done manually -

calloc()allocates memory and zeroes it before returning -

realloc()is useful when you’ve allocated space (e.g., for an array) and need to add something to it

15 - Mechanism: Address Translation

hardware-based address translation - hardware interposes on each memory access (e.g., an instruction fetch, load, or store) changing the virtual address to a physical address where the data actually resides

- OS must be involved to set up hardware to manage memory

-

objdumpon Linux allows us to disassemble C to assembly

base and bounds (dynamic) relocation

- two hardware registers, a base register and a bounds/limit register

- this relocation happens at runtime and is thus dynamic (rather than static)

physical address = virtual address + base- if a process generates a virtual address that is greater than the bounds or one that is negative, the CPU will raise an exception

- memory management unit - the part of the processor that helps with address translation

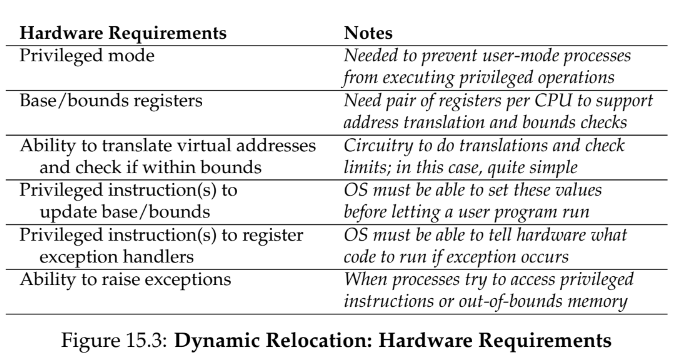

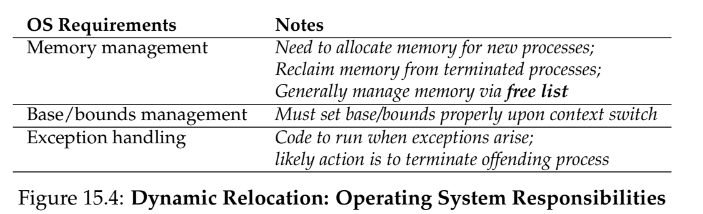

hardware support

os support

free list - a data structure that lists free space available internal fragmentation - base and bounds leads to wasted space within the allocated unit

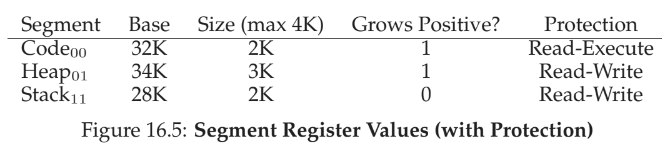

16 - Segmentation

- approach of using base and bounds is wasteful

- how can we support a large address space with free space between heap and stack?

- we can have base and bounds pair per logical segment of address space

- segment is a contiguous portion of address space of a particular length

- sparse address spaces - large amounts of unused address space in a large address space

- segmentation fault - violation from memory access on a segmented machine to an illegal address

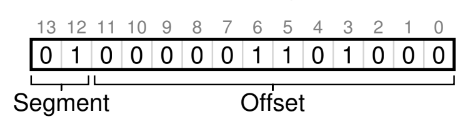

two approaches for hardware to determine which segment an address is in

-

explicit

- chop up address space into segments based on top few bits of virtual address

- first two bits are segment, remaining are offset into segment

- using two bits leaves one segment unused (00, 01, 10, 11 <- unused), so some systems put code in same section as heap and only use one bit to select

-

implicit

- hardware determines how the address was formed, e.g., addresses from program counter (instruction fetch) then address is within code segment

- hardware also needs to know which way segment grows to accommodate stack in addition to base and bounds registers

- to save memory, sometimes its useful to share memory segments between address spaces

- need protection bits to to indicate read or write permissions

fine-grained segementation - many smaller segments, but requires a segment table as a map course-grained segmentation - only a few segments, i.e., code, stack, heap

-

fine-grained segmentation gives more flexibility for more use cases

- external fragmentation - physical memory becomes full of little holes of free space, making it difficult to allocate or grow segments

- compact physical memory - rearrange existing segments to ease fragmentation

- compaction is expensive and copying segments is memory-intensive and uses a fair amount of processor time

- free list management algorithm - keep large extents of memory available for allocation

- other algorithms like best-fit, worst-fit, first-fit, buddy algorithm

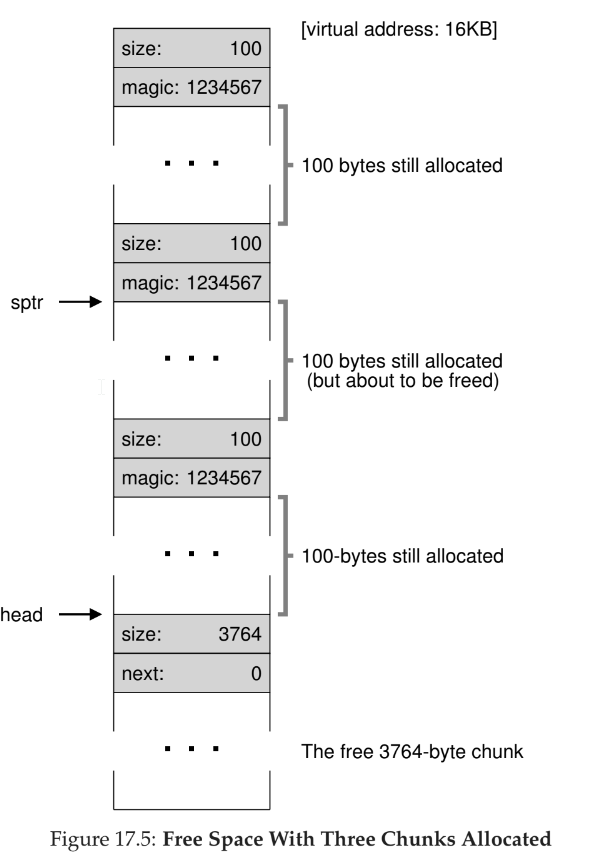

17 - Free Space Management

- managing space is easier if the space is divided into fixed-size units

- much harder when sizes are variable, such as user-level memory-allocation libraries like

malloc - problems are with external fragmentation

-

sbrksystem call grows heap

Low-Level Mechanisms

- splitting - memory allocator will find a free chunk of memory that can satisfy request and split in two

-

coalescing - when memory is freed, the memory allocator looks at adjacent chunks to see if freed space can be merged to an existing chunk

-

free()doesn’t take asizeparameter, so a header block is used to track that extra information -

header takes up a small amount of space on its own

- when a user requests N bytes of memory, the memory library searches for a free chunk of N bytes plus the header

1

2

3

4

typedef struct {

int size;

int magic; // for integrity checking

} header_t;

- a free list is created within the free space itself

- if you need to grow the heap, one option is to just fail and return NULL

- most traditional allocators start with a small heap and grow via

sbrkin most UNIX systems

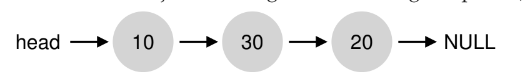

Basic Strategies

- ideal memory allocation strategy is fast and minimizes fragmentation

Best Fit

- search through free list and find chunks that are as big or bigger than request, and return smallest of those

- downsides are that you need to search the whole list

Worst Fit

- search through free list and find the largest chunk and break off the requested amount

- downsides are that you need to search the whole list, and most studies show it performs poorly and leads to excess fragmentation

First Fit

- search through free list and find the first block that is big enough

- fast, but can pollute the beginning of the free list with small objects

-

address-based ordering helps keep the beginning of the list clear by ordering the free list by address of free space

- coalescing is easier and fragmentation is reduced

Next Fit

- keep an extra pointer to last location searched

- searches through free space are more uniform

- similar performance to first fit

if searching for 15 bytes

- best fit picks 20

- worst picks 30

- first fit picks 30

Segregated Lists

- if application has popular-sized requests, keep a separate list to manage objects of that size

- an example is slab allocator

- allocates object caches for kernel objects that are likely to be requested ferquently (e.g., locks, file-system inodes, etc)

- when cache is running low, it asks for some slabs of memory from a general allocator

- freed memory will go back to general memory

- objects are kept in a pre-initialized state, as initialization and destruction of data structures is costly

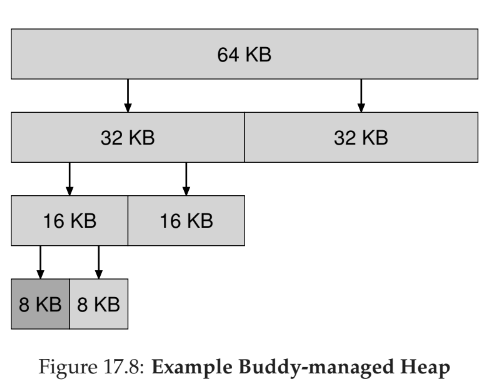

Buddy Allocation

- memory is one big space, and when memory is requested, space is divided by two until a suitable block is found

- key is that when memory is freed, allocator will check its buddies to see if it can be coalesced all the way up the tree

- most of these approaches have difficulty scaling, as searching can be quite slow

- glibc allocator is an example of a C allocator in real use

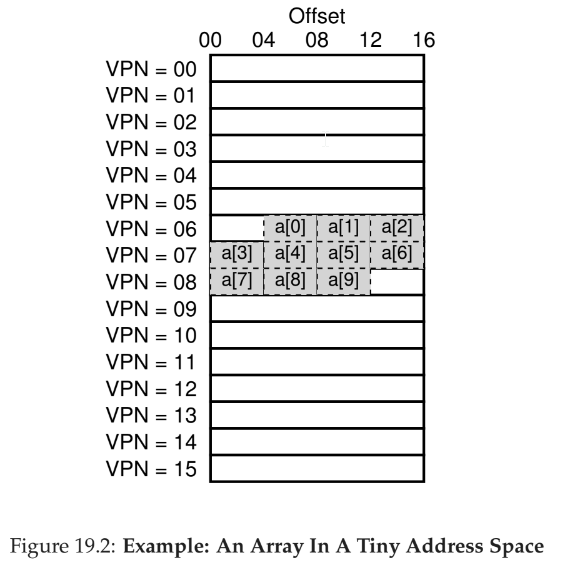

18 - Paging

- segmentation chops up data into variable-sized chunks, leading to fragmentation

- paging divides memory into fixed-sized chunks, each called a page

- physical memory is then an array of fixed-sized slots called page frames

- paging has several benefits:

- flexibility - the address space abstraction is fully supported, and no assumptions about how stack and heap grow need to be handled

- simplicity - just need to find free pages to use for address space

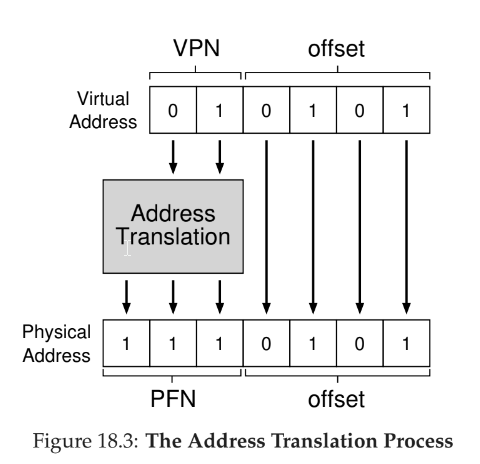

translation

- split virtual address into virtual page number (VPN) and offset

- replace the virtual page number with the physical frame number (PFN) (sometimes called the physical page number (PPN))

- offset tells us which byte within the page we want

page tables

- page table - per process data structure that the OS keeps to store address translations, which lets OS know where in physical memory a page resides

-

page table entry (PTE) - stores actual physical translation

- 20 bit VPN implies 2^20 translations, and at 4 bytes per PTE that is 4MB for each page table, and if there are 100 processes, thats 400MB

- they can get much larger than a small segment table or base/bounds pair

- simplest form is a linear page table, which is just an array

- OS indexes array by virtual page number and looks up the page-table entry at that index to find the physical frame number

- many different bits to to dictate behavior:

- valid bit - common to indicate whether the particular translation is valid

- protection bit - can the page be read from, written to, or executed from

- present bit - whether this page is in physical memory or on disk (i.e., has been swapped)

- dirty bit - whether page has been modified since brought into memory

- reference bit (accessed bit) - whether page has been accessed

- without careful design of both hardware and software, page tables cause system to run too slowly and take up too much memory

18 - Translation-Lookaside Buffers

- going to paging table for every address translation is costly

- translation-lookaside buffer (TLB) - part of the chip’s memory management unit (MMU) and is a hardware cache of popular virtual-to-physical address translations

TLB control flow algo

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

VPN = (VirtualAddress & VPN_MASK) >> SHIFT

(Success, TlbEntry) = TLB_Lookup(VPN)

if (Success == True) // TLB Hit

if (CanAccess(TlbEntry.ProtectBits) == True)

Offset = VirtualAddress & OFFSET_MASK

PhysAddr = (TlbEntry.PFN << SHIFT) | Offset

Register = AccessMemory(PhysAddr)

else

RaiseException(PROTECTION_FAULT)

else // TLB Miss

PTEAddr = PTBR + (VPN * sizeof(PTE))

PTE = AccessMemory(PTEAddr)

if (PTE.Valid == False)

RaiseException(SEGMENTATION_FAULT)

else if (CanAccess(PTE.ProtectBits) == False)

RaiseException(PROTECTION_FAULT)

else

TLB_Insert(VPN, PTE.PFN, PTE.ProtectBits)

RetryInstruction()

- extract virtual page number (VPN) from virtual address

- check if VPN in TLB

- if yes:

- extract page frame number (PFN)

- concatenate onto the offset from the virtual address

- access memory at physical address

- if no:

- check the page table for translation

- if not valid, raise exception

- update TLB

- retry from step 2

- hardware caches take advantage of spatial and temporal locality

- spatial locality - if a program accesses memory at address x, it will likely soon access memory near x.

- temporal locality - an instruction or data item that has been recently accessed will likely be re-accessed soon in the future

Who handles a TLB miss?

- either hardware or OS

hardware

- in older systems, hardware had a complex set of instruction sets (complex-instruction set computers CISC)

- hardware needs to know exactly where in memory a page table is via a page-table base register

- on miss, hardware walks page table, finds the relevant page table entry, updates TLB, and tires again

- example is Intel x86, which uses a multi-level page table

software

- more modern systems have limited instruction sets

- reduced-instruction set computers (RISC)

- on miss, hardware raises exception, traps into kernel and jumps to a trap handler

- unlike other traps which resume program excecution after the trap, when OS returns from trap it needs to start at where the call to memory started

- also needs to prevent infinite TLB calls – could use wired translations or unmapped handlers

- benefits are simplicity and flexibility

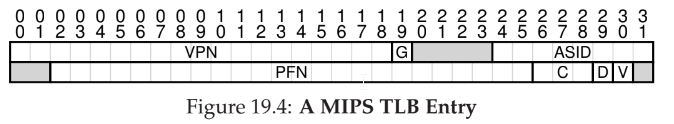

fully-associative cache - any given translation can be anywhere in the TLB (compared to direct-mapped cache entries, which are indexed, or less permissive set-associative caches)

How to handle context switches

- when a process is context switched, the TLB entries will be incorrect for the new process’s page table

- can simply flush the TLB, but this is expensive and not performance

- system can provide an address space identifer (ASID) to associate a TLB entry with process

- processes can share code and thus point to same physical frame number

Cache replacement

- least recently used (LRU)

- random - simpler, avoidance of corner-cases

exceeding TLB coverage - if number of pages a program access exceeds number of pages that fit into TLB, many misses will occur

20 - Paging: Smaller Tables

- page tables without any optimizations are too large and consume too much memory

- simple solution: use bigger tables, but this leads to waste within each page (internal fragmentation, as waste is internal to the unit of allocation)

Hybrid: Paging and Segments

- have a page table for each logical segment instead of the whole address space

- base (from base and bounds/limits) points to the physical address of the page table (rather than where in physical memory address space begins)

cost of paging and segments

- segmentation is not as flexible as possible as it assumes a certain usage pattern of the address space

- also causes external fragmentation to occur

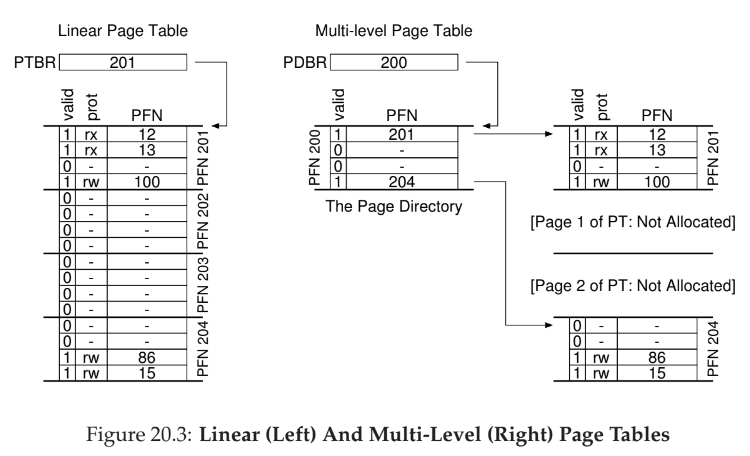

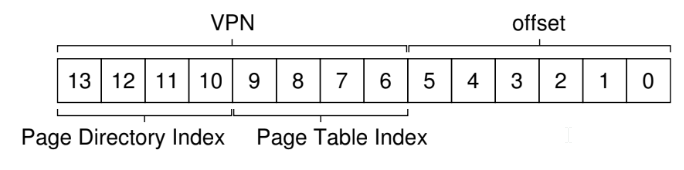

Multi-level Page Tables

- turns the linear page table into something like a tree

- chop up page table into page-sized units, then, if entire page-table entries (PTE) is invalid, don’t allocate that page

- introduces a page directory which holds whether page table is valid and where it is in physical memory

- page directory contains one entry per page of the page table (page directory entries (PDE))

- a page directory entry has a valid bit and a page frame number (PFN)

- for a large page table, it is difficult to find continguous memory, but page directory allows for level of indirection where we can put page-tables anywhere in physical memory

- you can also have more than two levels, but you need to increase VPN size

- how many page table entires fit within a page, and use that as index

cost of multi-level page tables

- time-space trade-off: less time equals more space, and vice versa – on TLB miss, two loads from memory will be required (one for page directory, and one for page table entry (PTE))

- adds complexity in OS or hardware handling lookup

PDEAddr = PageDirBase + (PDIndex * sizeof(PDE))

PTEAddr = (PDE.PFN << SHIFT) + (PTIndex * sizeof(PTE))

multi-level page table control flow

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

VPN = (VirtualAddress & VPN_MASK) >> SHIFT

(Success, TlbEntry) = TLB_Lookup(VPN)

if (Success == True) // TLB Hit

if (CanAccess(TlbEntry.ProtectBits) == True)

Offset = VirtualAddress & OFFSET_MASK

PhysAddr = (TlbEntry.PFN << SHIFT) | Offset

Register = AccessMemory(PhysAddr)

else

RaiseException(PROTECTION_FAULT)

else // TLB Miss

// first, get page directory entry

PDIndex = (VPN & PD_MASK) >> PD_SHIFT

PDEAddr = PDBR + (PDIndex * sizeof(PDE))

PDE = AccessMemory(PDEAddr)

if (PDE.Valid == False)

RaiseException(SEGMENTATION_FAULT)

else

// PDE is valid: now fetch PTE from page table

PTIndex = (VPN & PT_MASK) >> PT_SHIFT

PTEAddr = (PDE.PFN << SHIFT) + (PTIndex * sizeof(PTE))

PTE = AccessMemory(PTEAddr)

if (PTE.Valid == False)

RaiseException(SEGMENTATION_FAULT)

else if (CanAccess(PTE.ProtectBits) == False)

RaiseException(PROTECTION_FAULT)

else

TLB_Insert(VPN, PTE.PFN, PTE.ProtectBits)

RetryInstruction()

Inverted Page Tables

- instead of having many page tables (one per process), use a single page table that has an entry for each physical page of the system

21 - Beyond Physical Memory: Mechanisms

- in order to support larger address spaces, OS needs a place to stash additional portions of address space that isn’t in great demand

- modern systems use hard disk drive for this

- older systems used memory overlays, which required programmers to manually move pieces of code or data in and out of memory

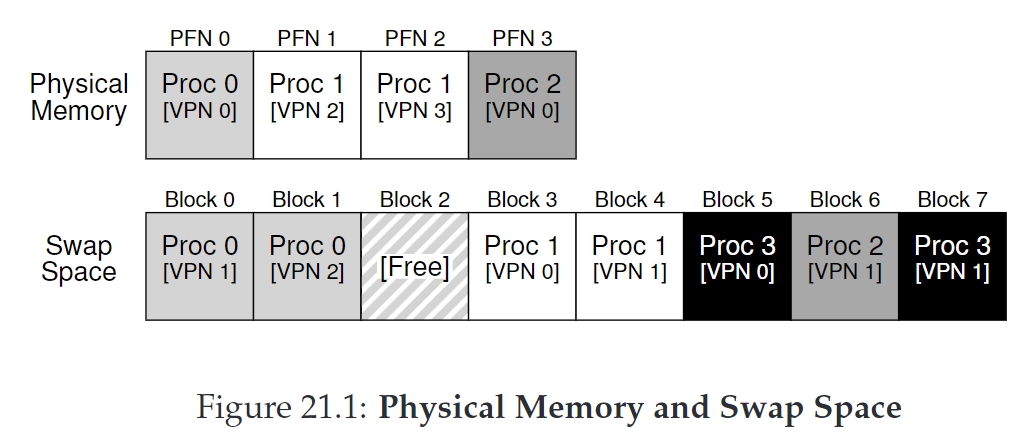

Swap Space

- allows OS to support the illusion of large virtual memory for multiple concurrently-running processes

- swap pages out of memory to a space, and swap pages into memory from it

-

present bit - additional piece of data in the page-table entry (PTE) that says whether data is in memory or in swap space

- if set to 1, the page is present in physical memory; 0, it is not in memory but on disk somewhere

Page Faults

- accessing a page that is not in physical memory triggers a page fault, and resolution is handled via a page-fault handler

- page faults typically handled by operating system (rather than hardware) because:

- page faults to disk are slow, so additional overhead of OS instructions are minimal

- hardware would need to understand swap space, how to issue I/Os to the disk, and other details

3 cases when a TLB miss occurs

- page present and valid -> update TLB, try again

- page not present -> page-fault handler

- page not valid -> seg fault

Page-Fault Control Flow Algorithm (Hardware)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

VPN = (VirtualAddress & VPN_MASK) >> SHIFT

(Success, TlbEntry) = TLB_Lookup(VPN)

if (Success == True) // TLB Hit

if (CanAccess(TlbEntry.ProtectBits) == True)

Offset = VirtualAddress & OFFSET_MASK

PhysAddr = (TlbEntry.PFN << SHIFT) | Offset

Register = AccessMemory(PhysAddr)

else

RaiseException(PROTECTION_FAULT)

else // TLB Miss

PTEAddr = PTBR + (VPN * sizeof(PTE))

PTE = AccessMemory(PTEAddr)

if (PTE.Valid == False)

RaiseException(SEGMENTATION_FAULT)

else

if (CanAccess(PTE.ProtectBits) == False)

RaiseException(PROTECTION_FAULT)

else if (PTE.Present == True)

// assuming hardware-managed TLB

TLB_Insert(VPN, PTE.PFN, PTE.ProtectBits)

RetryInstruction()

else if (PTE.Present == False)

RaiseException(PAGE_FAULT)

Page-Fault Control Flow Algorithm (Software)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

PFN = FindFreePhysicalPage()

if (PFN == -1) // no free page found

PFN = EvictPage() // run replacement algorithm

DiskRead(PTE.DiskAddr, PFN) // sleep (waiting for I/O)

PTE.present = True // update page table with present

PTE.PFN = PFN // bit and translation (PFN)

RetryInstruction() // retry instruction

Page-Replacement Policy

- if memory is full, need a way to evict/replace pages

- typically an active process, handled by a swap/page daemon

- high watermark and low watermark – if there are fewer than LW pages, a background process evicts pages until there is HW pages available

- many replacements happen at once, which allows for performance optimizations by clustering (which reduces seek and rotational overheads of a disk)

22 - Beyond Physical Memory: Policies

Cache Management

main memory holds some subset of all pages, can be though of as a cache for virtual memory pages in system goal is to minimize number of cache misses (how many times fetch a page from disk) average memory access time (AMAT) - AMAT = Tm + (Pmiss * Td) - Tm: cost of accessing memory - Pmiss: probability of cache miss - Td: the cost of accessing disk

3 types of cache misses:

- cold-start/compulsory - cache is empty to begin with, and this is first reference to item

- capacity - cache ran out of space and had to evict an item

- conflict - results in hardware because of limits on where an item can be placed in hardware cache (due to set-associativity) – OS page cache is fully-associative so no conflict misses happen

Optimal Replacement Policy

- replace/evict page that will be accessed furthest in the future results in fewest cache misses, unfortunately really hard to implement

- FIFO - performs poorly compared to optimal – doesn’t determine importance of blocks

- Random - a little better than FIFO but worse than optimal

Using History: Least Recently Used

- use history like frequency (how often a page is accessed) or recency (how recently a page was accessed)

-

principle of locality - programs tend to access certain code sequences and data structures quite frequently, and we should use history to determine what pages are or aren’t important

- spatial locality (data tends to be accessed in clusters)

- temporal locality (data tends to be accessed close in time)

- least frequently used (LFU) - how often a page is accessed

- least recently used (LRU) - when a page was most recently used

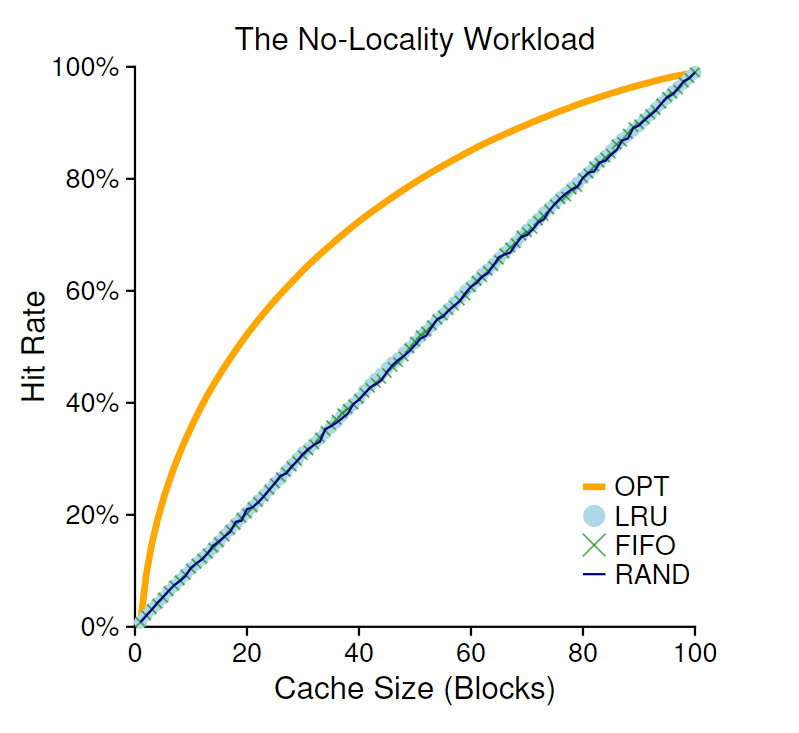

No Locality Workload

- each access is to a random page

- when there is no locality in workload or the cache is large enough to fit all data, lru, lfu, random, and fifo perform the same

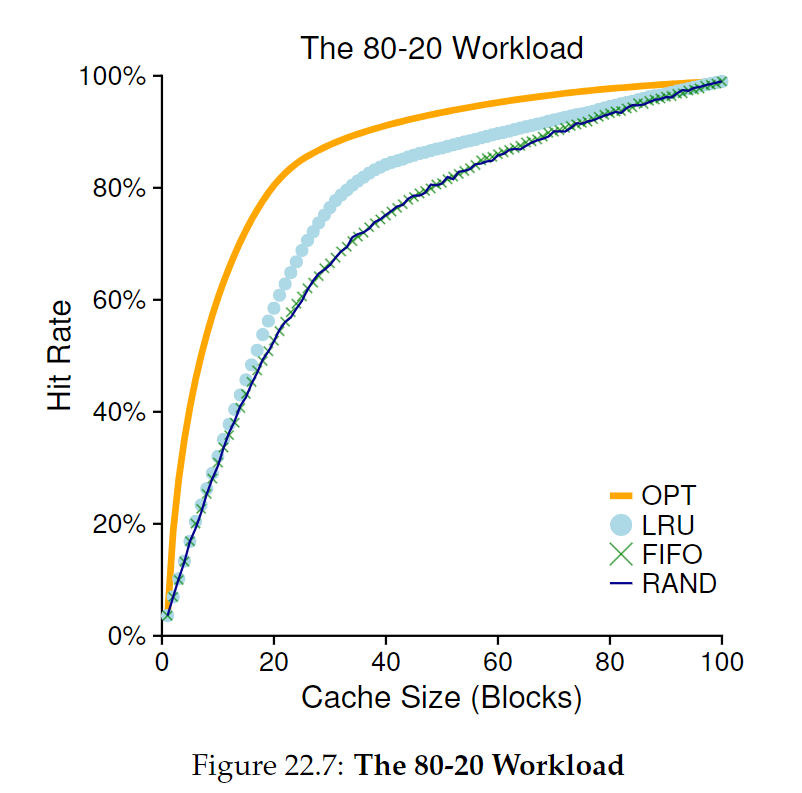

80-20 Workload

- 80% of accesses to 20% of pages (hot pages), 20% to the remaining 80% (cold pages)

- LRU does the best, and while improvement might seem minor it would lead to substantial performance gains

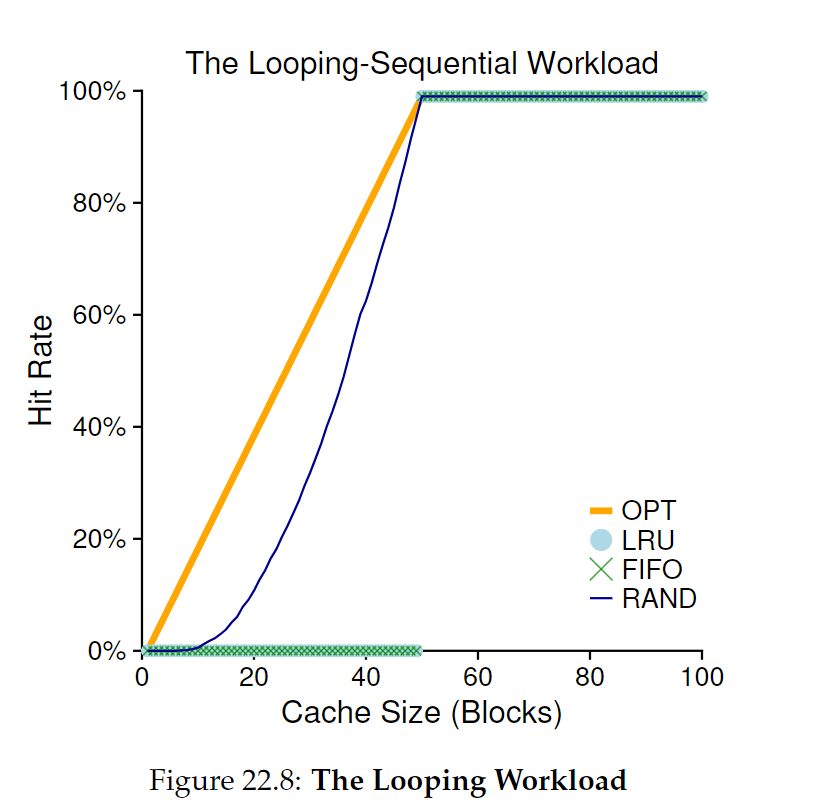

Looping Sequential Workload

- refer to n pages in sequence, then start again

- common workload for databases

- worst case for LRU and FIFO, random performs best

LRU performance

- to implement LRU perfectly, you’d need a data structure that stores when a page was last accessed, and it would need to be updated every memory reference – this can be bad performance; even if you get hardware support to store last access, scanning all pages would take a long time

- more performance algorithms are scan resistant - don’t need to scan entire data structure to find relevant data

- can approximate LRU using a use bit - on page access, use bit is set to 1, and when searching for a page to evict, the OS checks each page and if use bit is set to 1, it sets it to 0 and moves on until it finds a page with a use bit set to 0

- also could consider dirty (modified) pages, as if memory structure has been modified, it needs to be written back to disk to evict, which is costly – could prefer clean pages to evict

Other Memory Policies

- demand paging - OS brings page into memory when it is accessed, compared to prefetching, where an OS guesses when a page might be accessed before it is demanded

- when to write page to disk – clustering/grouping of writes is more performant

Thrashing

- when memory demands of running process exceeds available system memory, the system will be constantly paging

- admission control - a system might decide not to run a subset of processes, with the idea that reducing a processes’s working sets would fit into memory – do less but better

- out-of-memory killer - some Linux machines just kill off a memory-intensive process

23 - Complete Virtual Memory Systems

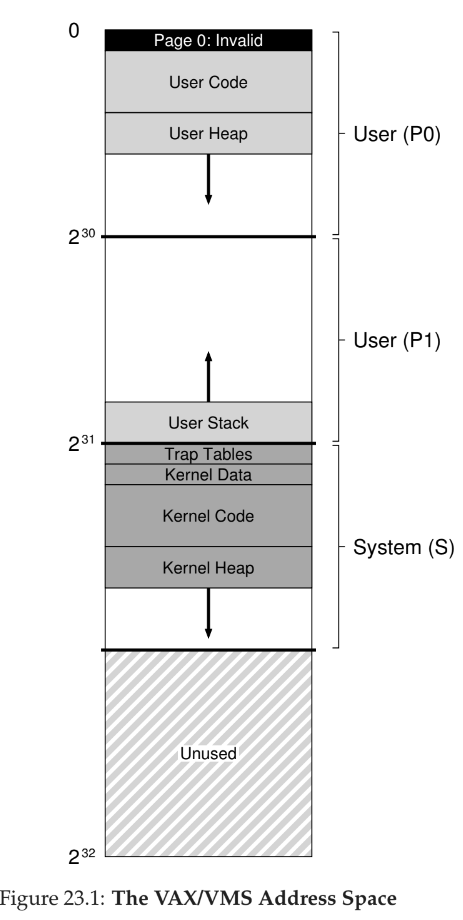

VAX/VMS Virtual Memory

- introduced in late 1970s by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC)

- uses a hybrid of paging and segmentation

Address Space

- lower half of address space called “process space” and is unique to each process

- first half of process space (P0) contains user program and heap data and grows downwards

- second half (P1) contains stack and grows upwards

- upper half of address space called system space (S)

- only half used

- contains OS data, and is shared across processes

- page 0 is reserved to aid in finding NULL pointer accesses

- because page tables can be allocated from kernel memory, translation is difficult – hopefully TLB handles each translation

Page Replacement

- page table entry contains

- a valid bit

- a protection field (4 bits)

- a modify bit

- an OS-reserved field (5 bits)

- a physical frame number (PFN) to store location of page in physical memory

- NO REFERENCE BIT!

- uses a segmented FIFO policy

- each process has max pages it can keep in memory (resident set size RSS)

- there is a second-chance list where pages that have fallen off the queue go (clean-page free list and dirty-page list)

- if new process needs a page, it takes it off clean list (unless original process needs that page again first)

- the bigger the second-chance lists are, the closer FIFO performs to LRU

Other Optimizations

- demand zeroing - instead of clearing out a page immediately for another process to use, this happens lazily upon demand, which saves effort if the page is never read or written

- copy-on-write - when OS needs to copy one page from one address to another, it maps it and marks as read-only – if it only needs to be read, it saves effort

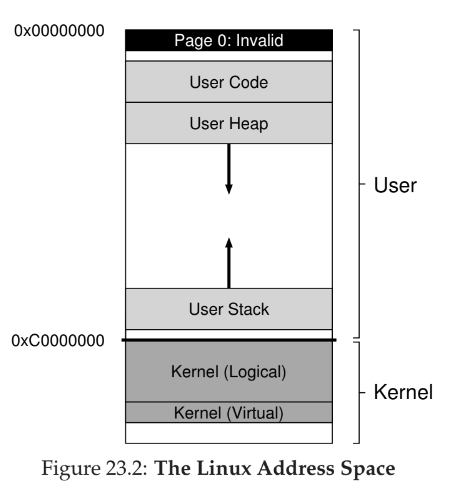

Linux

- divided between user and kernel portions of address space

- two types of kernel virtual addresses

- kernel logical addresses - contains most kernel data structures like page tables, per-process kernel stacks, apportioned by

kmallocand cannot be swapped to disk - kernel virtual address - usually not contiguous, apportioned by

vmallocand used to allow the kernel to address more than ~1GB of memory (limitation of 32 bit system not much relevant anymore)

- kernel logical addresses - contains most kernel data structures like page tables, per-process kernel stacks, apportioned by

Page Tables

- provides hardware-managed, multi-level page table structure – one page table per process

- OS sets up mappings in memory and points register at the start of the page directory, hardware handles the rest

- OS is involved in process creation, deletion, context switches

- support for huge pages beyond the typical 4KB page

- useful for certain workloads like databases

- limits TLB misses and makes TLB allocation faster

- could lead to large internal fragmentation, and swapping doesn’t work well as I/O is expensive

Page Cache

- unified, and keeps pages in memory from three sources

- memory-mapped files

- file data and metadata from devices (tracked from read() or write() calls)

- heap and stack pages for processes (called anonymous memory because no named file backing store)

- uses a 2Q replacement algorithm

- keeps two lists and divides memory between

- first time pages are put into inactive list

- when page is re-referenced, it is promoted to active list

- replacements are pulled from inactive list

- not typically managed in perfect LRU order, but typically uses a clock algo to prevent full scans

Security

- buffer overflow - allows attacker to insert arbitrary data into target’s address space, and usually occurs when developer assumes input won’t be overly long and inserts into a buffer – can trigger a privilege escalation, which gives attacker access to privileged mode

- return-oriented programming - lots of pieces of code (gadgets) in program’s address space, and by changing return address, attacker can string together gadgets to execute arbitrary code – combatted by address space layout randomization (ASLR) which randomizes virtual address layout