Clean Architecture

Table of contents

- Part I: Introduction

- Part II: Programming Paradigms

- Part III: Design Principles

- Part IV: Component Principles

-

Part V: Architecture

- Chapter 15: What is Architecture?

- Chapter 16: Independence

- Chapter 17: Boundaries: Drawing Lines

- Chapter 18: Boundary Anatomy

- Chapter 19: Policy and Level

- Chapter 20: Business Rules

- Chapter 21: Screaming Architecture

- Chapter 22: The Clean Architecture

- Chapter 23: Presenters and Humble Objects

- Chapter 23: Partial Boundaries

- Chapter 26: Layers and Boundaries

- Chapter 27: The Main Component

- Chapter 28: Services Great and Small

- Chapter 28: The Test Boundary

- Chapter 29: Clean Embedded Architecture

- Part V: Details

Part I: Introduction

Chapter 1: What is Design and Architecture?

Traditionally, architecture seems to imply high level details, while design is low-level structures and details, but little details support high-level details– it’s all part of the same whole of the system.

The goal of software architecture is to minimize the human resources required to build and maintain the required system.

The measure of design quality is measure of effort required to meet needs of customer.

Developers tell themselves two lies:

- “We can clean it up later; we just have to get to market first” – never clean it up because market is always moving

- writing messy code is faster than clean code – it never is

“The only way to go fast is to go well”.

Summary

Avoid overconfidence and take software design seriously.

In order to take software design seriously, you need to know what good design and architecture is – you need to know attributes of a system that minimizes effort and maximizes productivity.

Chapter 2: A Tale of Two Values

Every software system provides two different values to stakeholders:

Behavior

- the way a system behaves, written in a functional specification or requirements document then written in code

- when system doesn’t behave the way it is supposed to, programmers then debug

Architecture

- software of a system, subject to change

- difficulty in making a change should be proportional to the scope of the change, not shape

- new requirements roughly fit the same scope, but they often no longer fit the shape of the system and thus are increasingly difficult

- architectures should be as shape-agnostic as practical

Is a system working (behavior) or the ease of change (architecture) more important? If a program is impossible to change, it will become useless, but if it is easy to change, it can be made useful.

Eisenhower’s Matrix

| important & urgent | important & NOT urgent |

| NOT important & urgent | NOT important & NOT urgent |

- behavior is urgent but not always particularly important

- architecture is important but never particularly urgent

Business managers are not equipped to evaluate the importance of architecture, so it is responsibility of software dev team to assert importance of architecture over urgency of features.

Part II: Programming Paradigms

Chapter 3: Paradigm Overview

Structured Programming

- discovered by Edsger Wybe Dijkstra in 1968

-

gotostatements harmful to program structure, replace withif/then/elseanddo/while/untilconstructs - “Structured programming imposes discipline on the direct transfer of control”

Object-Oriented Programming

- discovered by Ole Johan Dahl and Kristen Nygaard in 1966

- “Object-oriented programming imposes discipline on the indirect transfer of control”

Functional Programming

- discovered before computers by Alonzo Church who in 1936 invented $ \lambda$-calculus (lambda calculus)

- typically no assignment statements

- “Functional programming imposes discipline on assignment”

Patterns typically take something away and are negative in intent, meaning there likely isn’t anything else to take away and there won’t be any other paradigms. All three were invented before 1968 and there’s been nothing since.

Summary

- we use polypmorphism to cross architectural boundaries

- we use functional programming to impose discipline on the location of and access to data

- we use structured programming as the algorithmic foundation of our modules

Chapter 4: Structured Programming

Dijkstra saw that programming was hard, and the cognitive load was too high to keep all details in mind at once. His answer was to use the mathematical discipline of proof, or the idea of using composable elements to create programs.

The use of goto prevented a program from being able to be decomposed recursively, and that good uses of goto really corresponded to if/then/else or do/while control structures.

All programs can be built from three elements: sequence, selection, and iteration.

Eventually, goto was phased out, and we are all ‘structured’ programmers in the sense that languages don’t give us the option to use undisciplined direct transfer of control.

Proofs ended up being too difficult, but the scientific method replaced proofs. The central idea is that things are falsifiable but not provable, as in, you can only prove something is false rather than proving it is true.

Dijkstra: “Testing shows the presence, not the absence, of bugs”.

Structured programming allows us to decompose a program into small provable functions that are falsifiable, i.e., testable.

Summary

Ability to create falsifiable units of programming that makes structured programming valuable today, and the reason unrestrained gotos aren’t used.

Functional decomposition is great practice.

Software is like a science, from low to high level, and is driven by falsifiability. Architects define modules, components, and services that are easily testable (falsifiable), using restrictive disciplines.

Chapter 5: Object-Oriented Programming

What is OOP? Some say “combo of data and function”, but that implies that o.f() is different from f(o) , which is absurd. Others say it is a way to model real world, but this is too loose and evasive.

Many say it is attributes of polymorphism, encapsulation, and inheritance.

Encapsulation

Being able to draw a cohesive line around data and functions, seen as private data members and public functions of a class.

Perfect encapsulation exists in C, a non-OO language. Data structures and functions would be declared in header files and implementation files would take care of the details, and users didn’t have access to implementation files. Once OO was introduced with C++, you lost perfect encapsulation.

Introducing public, private, and protected keywords a way to regain encapsulation, but this is a hack. Many OO languages have little or no encapsulation.

Inheritance

Inheritance is simply the redeclaration of a group of variables and functions within an enclosing scope.

OO languages allow for easier inheritance that isn’t a workaround, as well as multiple inheritance, but this functionality exists in non-OO languages

Polymorphism

Giving a single interface to entities of different types (think, file interface in Unix)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

struct FILE {

void (*open) (char* name, int mode);

void (*close) ();

int (*read) ();

void (*write) (char) ;

void (*seek) (long index, int mode);

}

Polymorphism is an application of pointers to functions, which have been in use for a long time. OO allowed this to be much safer, however, as pointers to functions are dangerous, relying on manual conventions. OO eliminates these conventions.

Unix chose to make IO devices plugins (polymorphism allows things to becomes plugins to the source code) because device independent programs are more adaptable. For example, punch cards to magnetic tape. Most OS’s implement this device independence.

Dependency Inversion

In typical calling tree, high level functions call mid level functions, which call low level functions, etc. The caller was forced to mention the name of the module that contained the callee, meaning that the flow of control was dictated by the behavior of the system.

Polymorphism means any source code dependency, no matter where it is, can be inverted. What this means is that working in systems written in OO languages have absolute control over direction of all source code dependencies.

Database and UI depend on the Business Rules, and from here components can be deployed independently.

Summary

OO is the ability, through the use of polymorphism, to gain absolute control over every source code dependency in the system. Architect can create plugin architecture where modules that contain high-level policies are independent of modules that contain low-level details, and all these modules can be deployed independently.

Chapter 6: Functional Programming

We might write a program to compute squares in Java like this:

1

2

3

for (int i=0; i <25; i ++>) {

System.out.println(i*i);

}

In Clojure, a derivative of Lisp, it’d look like this:

1

(println (take 25 (map (fn [x] (* x x)) (range))))

The key to functional programming is that variables do not vary (are immutable). In Java, the i variable mutates.

Immutability and Architecture

All race conditions, deadlock conditions, and concurrent update problems are due to mutable variables, and if no variable is ever updated you can’t have these concurrency problems.

We might be able to make everything immutable, if we had infinite storage and infinite processing power.

One compromise is to split mutable and immutable components, and to protect the mutable component by using a transaction or retry-based memory in front of that mutable component.

Architects should push as much processing as possible to immutable components.

Event Sourcing

Store only the transactions, and re-compute the state as needed. For example, banks store withdrawals and debits, and if the account balance is needed, all the debits and withdrawals are tallied. Nothing is ever deleted or updated, instead of CRUD we have CR.

This is the way source control system works.

Summary

Each paradigm takes something away. We have learned what not to do, but software is not a rapidly advancing tech, and the rules are the same as they were in 1946. Software is still composed of sequence, selection, iteration, and indirection.

Part III: Design Principles

SOLID principles tell us how to arrange functions and data into classes. The goal of the principles is the creation of mid-level software structures that:

- tolerate change

- are easy to understand

- are the basis of components that can be used in many software systems

SOLID Principles

SRP: The Single Responsibility Principle

- each software module has one, and only one, reason to change

OCP: The Open-Closed Principle

- systems should be easy to amend by adding new code, not changing existing code

LSP: The Liskov Substitution Principle

- to build a software system from interchangeable parts, those parts must adhere to a contract that allows those parts to be substituted for one another

ISP: The Interface Segregation Principle

- avoid depending on things you don’t use

DIP: The Dependency Inversion Principle

- code that implements high-level policy should not depend on the code that implements low-level details but rather should rely on policies

Chapter 7: SRP: Single Responsibility Principle

“A module should be responsible to one, and only one, actor.”

A module is a cohesive set of functions and data, typically a source file.

Best to look at symptoms of violating this principle.

Symptom 1: Accidental Duplication

Three different actors responsible for three different methods - accounting department for calculatePay(), human resources for reportHours(), and DBAs for save(). If two methods rely on the same underlying algorithm, changing it will change its affect on both methods, which might cause problems.

Symptom 2: Merges

If there are two actors that need to change a source file and those file changes need to be merged together, this is a symptom of violation of SRP.

There are a few solutions to this problem, and they all involve separating the code from the single class. We could create three classes, one for each method, and then thread them together using the Facade pattern.

Summary

SRP is about functions and classes, but it appears at two more levels:

- at components, it becomes Common Closure Principle

- at architectural, it is Axis of Change (responsible for creating Architectural Boundaries)

Chapter 8: OCP: The Open-Closed Principle

“A software artifact should be open for extension but closed for modification”

The behavior of a software artifact should be extendible without having to modify that artifact.

When we design architecture, we want component relationships to be unidirectional, and components that should be protected from change should be depended on by lower level components, i.e., if component A should be protected from changes in component B, component B should rely on component A.

At the architectural level, we separate functionality based on how, why, and when things change, and then organize that separated functionality into a hierarchy of components. High-level components are protected from changes made to low-level components.

Summary

The goal of OCP, one of the driving forces behind architecture of systems, is to make the system easy to extend without incurring a high impact of change. We partition the system into components, and arrange those components in a dependency hierarchy that protects higher-level components from changes in lower-level components.

Chapter 9: LSP: The Liskov Substitution Principle

“What is wanted here is something like the following substituion property: If for each object o1 of type S there is an object o2 of type T such that for all programs P defined in terms of T, the behavior of P is unchanged when o1 is substituted for o2 then S is a subtype of T.”

The following design conforms to LSP because Billing does not depend in any way on the two subtypes of License.

The canonical violation of LSP, the Square/Rectangle problem below:

Summary

LSP should be extended to the level of architecture. Violating substitutability can cause a system’s architecture to be polluted with a significant amount of extra mechanisms.

Chapter 10: ISP: Interface Segregation Principle

“No client should be forced to depend on methods it does not use.”

Source code dependencies are often language dependent: in statically typed languages like Java, programmers declare source code dependencies, and changes would force recompile and redeploy. In dynamically typed languages like Python and Ruby, these dependencies are inferred at runtime and thus allow more flexible and loosely coupled systems to be created.

ISP still has architectural ramifications, however: imagine System S implementing Framework F on top of Database D. Changes to Framework F, even if System S doesn’t use them, might require redeploys to Database D and System S.

Chapter 11: DIP: The Dependency Inversion Principle

“The most flexible systems are those in which source code dependencies only refer to abstractions, not concretions.”

While we can’t completely avoid relying on concretions (String in Java, for example), we should be worried about volatile concrete elements, those subject to frequent change. We can rely on stable abstractions and reduce the volatility of interfaces by adding functionality to implementations without making changes to interfaces.

This boils down to a specific set of coding practices:

- Don’t refer to volatile concrete classes - refer to abstract classes instead

- Don’t derive from volatile concrete classes - corollary of previous rule

- Don’t override concrete functions - concrete functions require source code dependencies, and overriding them does not eliminate those dependencies, you inherit them

- Never mention the name of anything concrete and volatile - a restatement of the principle itself

We use Factories to manage the dependency and create the class. This allows us to separate the system into two components, one concrete, the other abstract.

Summary

DIP is the most visible organizing principle in architecture diagrams, and the separation between concrete and abstract will inform all diagrams. The Dependency Rule is the way in which dependencies cross from concrete to more abstract in a single direction.

Part IV: Component Principles

Chapter 12: Components

Components are the units of deployment. jar files in java, gem files in Ruby, DLL in .NET. In compiled languages, they are aggregation of binary files, and in interpreted languages they are aggregations of source files.

Well-designed components retain the ability to be independently deployable and thus independently developable.

Chapter 13: Component Cohesion

Three principles of component cohesion:

-

The Reuse/Release Equivalence Principle (REP)

- people who want to reuse software components can not and will not do so unless those components are tracked through a release process and are given release numbers, and developers might choose to upgrade or not based on change log

- from arch. view, classes and modules that are formed into a component must belong to a cohesive group; grouped classes and modules should be releasable together

-

The Common Closure Principle (CCP)

- “Gather into components those classes that change for the same reasons and at the same times. Separate into different components those classes that change at different times and for different reasons.”

- most of the time maintainability is more important than reusability, so gathering components that change at the same time together enhances maintainability

- SRP restated for components, as well as Open Closed principle (open for extension but closed for modification)

-

The Common Reuse Principle (CRP)

- Classes and modules that tend to be reused together belong in the same component

- CRP tells us more about which classes shouldn’t be part of a component – if classes and modules are together, they should be inseparable. \

- “Don’t depend on things you don’t need”

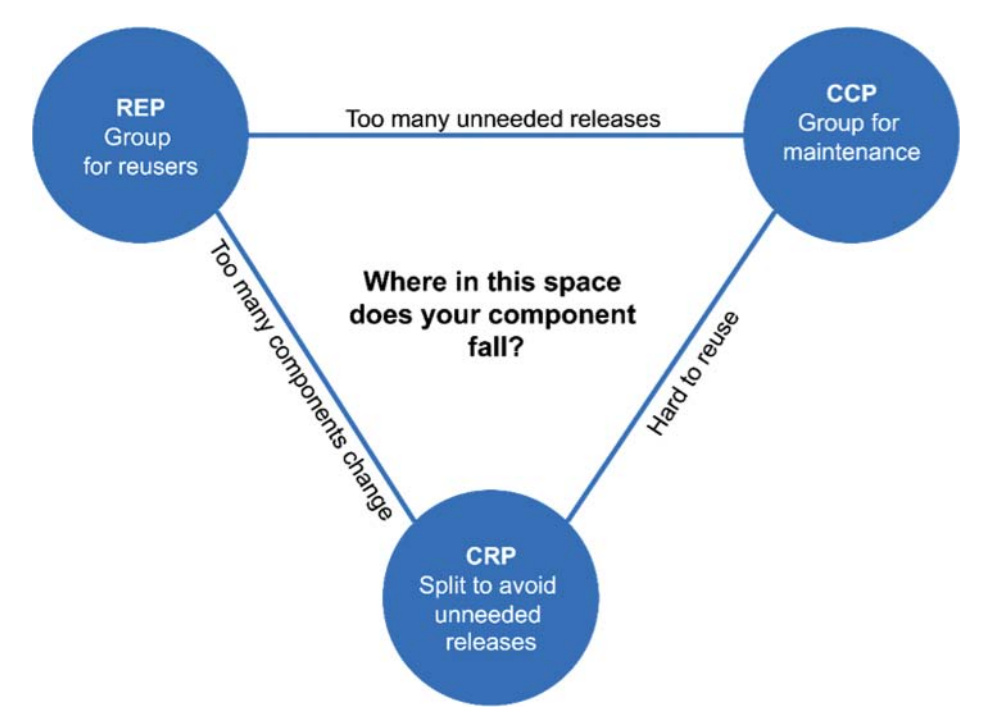

Tension Diagram for Component Cohesion

These principles are often in contention.

Chapter 14: Component Coupling

The Acyclic Dependencies Principle

In the past, there was an idea to allow relative isolation for developers to work collaboratively which was to defer that integration until the end of the week, i.e., a weekly build. Eventually, the integration time creeps earlier in the week, and the build schedule grows, and this is not ideal.

A solution to the above would be to partition development into releasable components owned by a single dev or a team of devs, so consuming teams might choose whether they want to update their used components.

Integration now happens in small increments, and no team is at the mercy of others; integration can be continuous.

In order to make this work, you need to manage the dependency structure, and there can be no cycles; regardless of what component you end up at, it is impossible to follow the dependency tree and end up at the original component. We need a directed acyclic graph (DAG).

We know how to build systems when we understand the dependencies between its parts.

With cycles in the dependency graph, it is very difficult to work out order in which you must build components.

There are two ways we could break the cycle:

- Use the dependency inversion principle (DIP) to create an interface of the used methods

- create a new component with the classes that the two components depend on

As systems grow, these dependencies will appear; the component structure can’t be designed from the top down. We have come to expect that large-grained decompositions like components, will also be high-level functional decompositions.

Decomposition in computer science, also known as factoring, is breaking a complex problem or system into parts that are easier to conceive, understand, program, and maintain.

In reality, component dependency diagrams have little to do with the function of a system, they are merely describing buildability and maintainability.

One of the overriding concerns is the isolation of volatility: we don’t want frequently changing components to affect stable, high-value components. We don’t want to change business rules because our GUI changes.

This process needs to happen after we’ve built the system a bit: we don’t know about common closure, we don’t know about reusable elements, and we almost certainly would create dependency cycles.

Stable Dependencies Principle

Ensures that modules that are intended to be easy to change are not depended on by modules that are harder to change.

Stability is related to the amount of work required to make a change.

Component X is stable, because three components depend on it. X is responsible for three components, but depends on none, so it is independent.

Component Y is very unstable. No components depend on it, so it is irresponsible, and it is dependent. Changes may come from three external sources.

Stability Metrics We can count the dependencies coming in and going out of a component, and this is the positional stability of the component

- Fan-in: incoming dependencies

- Fan-out: outgoing dependencies

- Instability: $ \int_0^1 I = Fanout \div (Fanin + Fanout) $

When I is equal to 1, no other component depends on this component – it is irresponsible and dependent, meaning there is no reason not to change it if needed

When I is equal to 0, it means the component is depended on by other components but does not itself depend on other components. It is responsible and independent (and stable) – lots of dependents make it hard to change and nothing forces it to change.

I metric of a component should be larger than the I metrics of the components that it depends on, that it should decrease in the direction of the dependency.

Changeable components on top and stable components on bottom.

The Stable Abstractions Principle

“A component should be as abstract as it is stable”

- $ Nc $: the number of classes in the component

- $ Na $: the number of abstract classes and interfaces in the component

- $ A $: abstractness.$ A = Na \div Nc $

Best components are maximally stable and abstract, and maximally unstable and concrete.

- Zone of Pain - highly stable, concrete – if these components are volatile (need to be changed often), this is painful

- Zone of Uselessness - maximally abstract but no dependents – these components are useless

Part V: Architecture

Chapter 15: What is Architecture?

A software architect is a programmer, the best programmer, and they continue to take programming tasks, because it is important they experience the problems they are creating for the rest of programmers.

The architecture of a software system is the shape given to that system by those who build it, and the purpose of the shape is to facilitate the development, deployment, operation, and maintenance of the software system.

“The strategy behind that facilitation is to leave as many options open as possible for as long as possible.”

The primary purpose of architecture is to support the life cycle of the system, and good architecture makes the system easy to understand, easy to develop, easy to maintain, and easy to deploy, to minimize lifetime cost and maximize programmer productivity.

development

systems need to be easy to develop, and this ease is dictated by different team structures. small teams might be predisposed to a monolith, while distributed teams to microservices.

deployment

a goal of architecture should be to make sure a system is deployable with a single action

some things might leave a system easy to develop but hard to deploy: e.g., microservices

operation

it is easier to scale out hardware to help operation, so its impact on architecture is less pronounced. hardware is cheap and people are expensive.

The architecture of a system makes the operation of the system readily apparent to the developers; it should reveal operation.

maintenance

likely the most costly aspect of software systems, and the primary cost is spelunking (digging through existing software, trying to find the best place and strategy to add a new feature or repair a defect) and risk.

Software has two types of value: behavior and structure. We keep software soft by leaving as many options open as possible. The details we leave open are the ones that don’t matter.

Every software system can be decomposed into two major elements: policy and details. Policy is where the value of the system lives, details enable computers or humans to communicate with policy, and the goal of architect is to make a system that recognizes policy as most essential, and ensures details are irrelevant to that policy. These details can be delayed and deferred, e.g., what database, whether REST compliant, web server, etc.

Chapter 16: Independence

Good architecture must support:

- use cases and operation of the system

- maintenance of the system

- development of the system

- deployment of the system

Use Cases

Architecture must support intent of the system. Architecture does not wield much influence over behavior, so best thing architecture can do is clarify and expose intent of the system and make it visible at the architectural level.

These exposed elements will be classes or functions that have prominent positions within architecture and will be clearly named to describe that.

Operation

A system must be structured to allow its operation, whether that is 100,000 customer orders per second or 2,000 records per second throughput. It is best to leave open decisions on system structure (monolith, microservices).

Development

“Any organization that designs a system will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure” - Conway’s Law

A system that must be developed by an organization with many teams and many concerns must have an architecture that facilitates independent actions by those teams.

Deployment

The goal is “immediate deployment”, achieved through the proper partitioning and isolation of the components of the system.

A good architecture supports use cases and balances that with a component structure that mutually satisfies them all. This is hard because all use cases are not known, so leaving the system open to change in all the ways it must change is important.

Decoupling Layers

Use SRP and CCP to separate components that change for different reasons and collect what changes for the same reasons, and divide those into decoupled horizontal layers.

Decoupling Use Cases

Group together use cases in the same way we did for components, and make those the vertical slices across your horizontal layers. We shouldn’t have to modify use cases, just add more.

Then, we can choose a decoupling mode – is it service-oriented architecture (SOA)? What needs to be run in the same address space, what can be separated to a different service? This option can be left open.

If decoupling is done well, it should be easy to hot-swap components in the live system. Adding a new use case should be as simples as adding a new jar file or service to the system.

Be wary of true duplication vs false duplication. If you have a change that needs to be reflected in all its duplicated elements, that is true duplication, but if you build an abstraction over duplicated code that is really two separate entities that evolve along separate paths, this is accidental duplication and can be largely ignored.

Decoupling Modes

- Source level - we can control dependencies between source code modules so changes to one don’t force changes or recomp. to others

- Deployment level - decoupled components are partitioned into independently deployable units such as jar files, gem files, or dlls

- Service level - reduce dependencies down to data structures and only communicate through network packets

How to choose? One method is to decouple at the service-level by default, but this is often a waste in effort, memory, and cycles (the first being most expensive).

Good architecture protects the majority of the source code from these changes, and leaves the option open as long as possible.

Chapter 17: Boundaries: Drawing Lines

Software architecture is the art of drawing boundaries that separate software elements from one another and restrict one side from knowing about those on the other. Coupling saps human resources required to build systems.

Draw lines between things that matter and things that do not. E.g., the database doesn’t matter to the GUI, so there should be a line between the two.

Some have thought that the database is the embodiment of the business rules, but that is false. The database is a tool that the business rules use indirectly. All the business rules need to know about is that there is a set of functions to fetch/save data.

We can draw a line across the inheritance relationship, just below the DatabaseInterface. The Database could be implemented with Oracle or MySQL or Couch or Datomic or flat files, and the business rules don’t care.

Also worth noting, IO is irrelevant.

This is all a plugin architecture, or the idea that we could swap layers as plugins to business rules.

Summary

To draw boundary lines in software architecture, you first partition the system into components. Some of those components are core business rules, others are plugins that contain necessary functions that are not related to the core business. Then you arrange the code in those components such that the arrows between them point in one direction – toward the core business.

Chapter 18: Boundary Anatomy

monolith - the simplest and most common architectural boundary, simply disciplined segregation of functions and data within a single processor and a single address space. From a deployment view, this is a single executable file.

Even in a monolith, OO paradigms allow us to decouple classes and function calls; dependencies cross boundaries towards the higher-level component.

Chapter 19: Policy and Level

Software systems are statements of policy: a program is a detailed description of the policy by which inputs are transformed to outputs.

Within a system are many smaller statements of policy, and architecture is separating those policies and regrouping based on the ways that they change, often in a directed acyclic graph, and the direction of those dependencies is based on the level of the components they connect. Low-level components to depend on high-level components.

A definition of level would be distance from the inputs and outputs. Higher level policies that are farthest from the inputs and outputs tend to change less frequently and for more important reasons, while lower level policies change more frequently and with more urgency but for less important reasons.

Chapter 20: Business Rules

If we divide our apps into business rules and plugins, what is a business rule? Simply they are rules or procedures that make or save money. They would make or save the business money even if implemented manually. E.g., a bank charging N% interest on a loan. These are Critical Business Rules, because they are critical to the business itself. These items typically need data, called Critical Business Data. Bounded together, they are an object called an Entity.

We can see Critical Business Data and Critical Business Rules together in the above class, although it doesn’t have to be a class – it could be any object.

Sometimes, business rules might only save money when used in an automated way. This is a use case, or a description of the way an automated system would be used. Use cases control when Critical Business Rules within entities are invoked. These use cases use the Request and Response model, where a use case accepts simple request data structures for its input and returns simple response data structures as its output.

Chapter 21: Screaming Architecture

If you look at a home, or a library, the architecture screams the function. A software application should scream about the use cases of the application.

A good architecture allows decisions about frameworks, databases, web servers, and other environmental issues and tools to be deferred and delayed.

Also, the Web is an IO device, not an architecture.

Frameworks are tools, not ways of life.

If your system architecture is all about use cases, you should be able to unit test all those use cases without any frameworks in place.

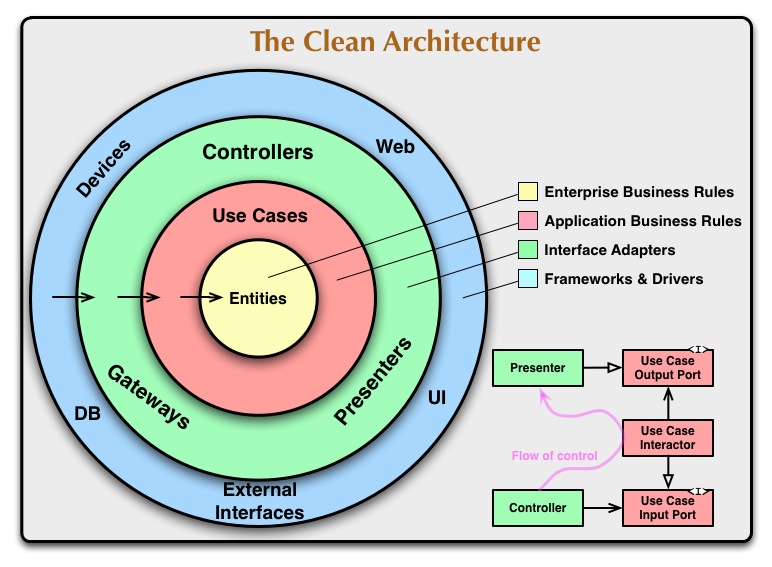

Chapter 22: The Clean Architecture

Most architectures try to achieve the same thing, separation of concerns, through dividing the system into layers that have the following characteristics:

- independent of frameworks

- testable

- independent of the UI

- independent of the database

- independent of any external agency

The further in you move, the higher level the software is.

“Source code dependencies must point only inward, toward higher-level policies.”

entities - describe enterprise-wide Critical Business Rules; can be object with methods, or set of data structures and functions use cases - contains application specific business rules, encapsulating and implementing all the use cases of the system interface adapters - converts data from a format most useful for use cases and identities to a format for some external agency framework and drivers - this is where all the details go, and there isn’t much code here other than glue code

isolated, simple data structures are passed across the boundaries – we don’t want the data structures to have any sort of dependency that violates the dependency rule.

Chapter 23: Presenters and Humble Objects

The Humble Object Pattern - originally used by unit testers to split the hard to test behaviors from the easy to test behaviors. we can use that to split into two modules or classes, the hard to test (humble) and the easy.

The GUI is hard to test, but the functionality isn’t. So splitting them gives us the Presenter and the View.

Code in the hard to test object (humble) is as simple as possible. The Presenter is the testable object. In this scenario, its role is to format data for presentation so the View can simply move it to screen. Everything that appears on the screen is presented as a string, a boolean, or an enum.

Where do ORMs belong? In the database layer, between gateway interfaces and the database.

Chapter 23: Partial Boundaries

Proper boundaries are expensive to create – you need to create reciprocal Boundary interfaces, Input and Output data structures, and all the dependency management to ensure the two sides are independently compilable and deployable. We can create partial boundaries to give us flexibility later (this might be a violation of agile’s YAGNI - you ain’t gonna need it).

Do all the work of creating the boundary but then keep it in the same component. Requires same amount of code, but not of administration of multiple components.

Another pattern is the Strategy pattern, or getting the boundary behavior at runtime.

Another pattern might be the Façade pattern, which sacrifices dependency inversion, where the Façade deploys service calls to classes the Client is not supposed to access.

Summary

Three ways to implement boundary:

- partial boundary

- one-dimensional boundary

- façade

each boundary can be degraded if that boundary never materializes. It is a function of an architect to decide where boundaries might one day exist.

Chapter 26: Layers and Boundaries

It’s easy to think a system is comprised of only three systems: UI, Business Rules, and Database, but there is more.

Chapter 27: The Main Component

Think of Main as a plugin to the application that sets up initial conditions and configurations, gathers all the outside resources, and then hands control over to the high-level policy of the application. There might be a Main plugin for dev, for test, for production. If we think of Main sitting behind an architectural boundary, configuration becomes a lot easier to reason about.

Chapter 28: Services Great and Small

Service-oriented and microservice architecture are popular in part because:

- services seem strongly decoupled from each other

- services appear to support independence of development and deployment

Using services isn’t an “architecture”. An architecture is defined by the boundaries that separate high-level policy from low-level details. Services might be part of an architecture, but they don’t define it.

the decoupling fallacy

It is a myth that services are fully decoupled. They might share resources within a processor or on a network, and they are certainly coupled by the data they share. If a new field is added to a data record passed between services, the receiving service needs to be changed.

Additionally, while interfaces are well-defined, so are they between functions. Services aren’t any more rigorously defined.

the fallacy of independent development and deployment

Teams can be solely responsible for writing, maintaining, and operating the service as part of a dev-ops strategy, and this is scalalable. This is only partially true.

- large orgs can be built on monoliths and component-based systems as well as service based

- services cannot always be independently developed, deployed, and operated (based on decoupling fallacy)

Chapter 28: The Test Boundary

Tests are part of the system. From an architectural standpoint, all tests are the same. We can think of tests as the outermost circle, and they follow the Dependency principle, as in, their dependencies point inward.

Tests tend to be tightly coupled to system code, so changes to common systems can cause hundreds or even thousands of tests to fail, called the Fragile Tests Problem, which has the effect of making the system rigid because people resist changes so tests don’t fail. Design for testability – don’t depend on volatile things, so build a system so tests don’t rely on volatile things.

One way to achieve this is to build a testing API so tests can verify business rules. This API will be a superset of interactors and interface adapters. We want to decouple the structure of the tests from the structure of the application.

This avoids the structural coupling of test and application.

Tests must be well-designed if they are to provide the desired benefits of stability and regression, and those tests that are not designed as part of the system tend to be fragile and difficult to maintain.

Chapter 29: Clean Embedded Architecture

“Although software does not wear out, firmware and hardware become obsolete, thereby requiring software modifications.”

Part V: Details

Chapter 30: The Database is a Detail

“From an architectural view, the database is a non-entity – it is a detail that does not rise to the level of an architectural element.” This doesn’t mean data models are details; those are highly significant to architecture.

Edgar Codd defined the principles of relational databases in 1970, and its very valuable technology.

Accessing things on memory is hard. Data access takes milliseconds, meaning you need indexes, caches, and query optimizers for fast and efficient access of data. This has taken two dominant forms: file systems and relational database management systems (RDBMS). File systems are document based, and they work well when you need to find a file by name but not search its contents. Databases are content based, and are good if you need to find a record by content.

Once disks go away, all data will be stored in RAM. The format it takes on RAM will be the format all programmers are used to and what data from tables is turned into: stacks, queues, linked lists, hash tables, trees, etc.

What about performance? When it comes to data storage, that concern can be encapsulated and separated from business rules. Efficient data access and storage is a low level concern.

The data is significant. The database is a detail.

Chapter 31: The Web is a Detail

Abstracting the business rules from the UI and web isn’t easy, but it can be done.

Chapter 32: Frameworks are Details

Frameworks are popular and useful, but they are not architectures.

The relationship between you and the framework author is asymmetric – you rely entirely on the framework and they don’t know you exist.

This is a weird chapter full of parasitic references of invasion.

You can use the framework, but try not to couple completely to it. Inject it into your Main component but leave it there.

Chapter 33: A Use Case

No notes for this chapter.

Chapter 34: The Missing Chapter

4 ways to package your application:

-

Package by Layer

- traditional horizontal-layered application

- layers only depend on lower adjacent layer

- good way to start a project, but problems are 1) you probably need to increase modularizing 2) it doesn’t scream its architecture

-

Package by Feature

- switch from horizontal to vertical layering

- closer to screaming architecture, but still problematic

-

Ports and Adapters

- like hexagonal, or boundaries, controllers, and entities architecture patterns

- business-domain-focused code is independent and separate from technical implementation details such as frameworks and databases

- inside contains domain concepts expressed in ubiquitous domain language, and the outside depends on the inside by never the other way around

-

Package by Component

- an additional way of packaging

- bundle up business logic and persistence code into single element, which is a mechanism to enforce certain access schemes (i.e., a controller not accessing a persistence layer around the service layer)