The Design of Everyday Things

1: The Psychopathology of Everyday Things

Chapter Summary

Every object has certain abilities (affordances) that object allows dependent upon the user of that object. There are ways to signal what those abilities are (signifiers), and how to create those is the key insight of designing. We should design for humans through human-centered design, without the rosy-colored idea that humans are perfect agents and should bend to the machines contours rather than the other way around.

norman doors - poorly designed doors where it isn’t clear if you should push or pull

two most important parts of design

- discoverability - is it even possible to figure out what actions are possible and where and how to perform them?

- understanding - what does it all mean? how is the product supposed to be used? what do all the different controls and settings mean?

All artificial things are designed (4)

Three Types of Design

- industrial design - The professional service of creating and developing concepts and specifications that optimize the function, value, and appearance of products and systems for mutual benefit of both user and manufacturer

- interactive design - The focus is upon how people interact with technology. The goal is to enhance people’s understanding of what can be done, what ishappening, and what has just occurred. Interaction design draws upon principles of psychology, design, art, and emotion to ensure a positive, enjoyable experience.

- experience design - The practice of designing products, processes, services, events, and environments with a focus placed on the quality and enjoyment of the total experience

It is the duty of machines and those who design them to understand people […] We have to accept human behavior the way it is, not the way that we would wish it to be. (6)

Human-Centered Design

- a design philosophy that puts human needs, capabilities, and behavior first, then designs to accommodate those needs, capabilities, and ways of behaving

Great designers produce pleasurable experiences. (10)

Fundamental Principles of Design

- discoverability - It is possible to determine what actions are possible and the current state of the device

-

affordances - The proper affordances exist to make the desired action possible

- the relationship between the properties of an object and the capabilities of the agent that determine how the object could be used

- e.g., a chair affords sitting, but a heavy chair might only afford lifting to a few

- importantly, it is not a property but a relationship – key is knowing who will use what you design

- are the possible interactions between people and the environment – some are perceivable, some are not

- perceived affordances often act as signifiers, but they can be ambiguous

-

signifiers - Effective use of signifier ensures discoverability, and that the feedback is well communicated and intelligible

- refers to any mark or sound, any perceivable indicator that communicates the appropriate behavior to a person

- affordances determine what actions are possible, signifiers communicate where the action should take place

- more important than affordances because they communicate how to use the design

- must be perceivable, otherwise they fail to function

- constraints - Providing physical, logical, semantic, and cultural constraints guides actions and eases interpretations

-

mappings - The relationship between controls and their actions follows the principles of good mapping, enhanced as much as possible through spatial layout and temporal contiguity

- the relationship between the elements of two sets of things

- e.g., a set of light switches and the lights they control, or the controls that move a car seat

- related controls should be grouped together, controls should be close to the item being controlled

-

feedback - There is full and continuous information about the results of actions and the current state of the product or service. After an action has been executed, it is easy to determine the new state.

- some way of letting you know the system is working on your request

- must be immediate

- must be informative

-

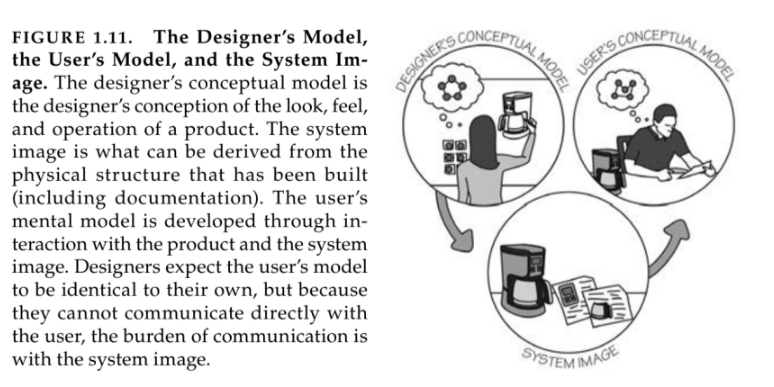

conceptual model - The design projects all the information needed to create a good conceptual model of the system, leading to understanding and a feeling of control. The conceptual model enhances both discoverability and evaluation of results

- an explanation, usually highly simplified, of how something works

- depending on your expertise, your conceptual model might be more or less right

system image

- the combined information available to us

- informed by the designer’s conceptual model, and informs the user’s conceptual model

the paradox of technology

The same technology that simplifies life by providing more functions in each device also complicates life by making the device harder to learn, harder to use. (34)

2: The Psychology of Everyday Actions

Chapter Summary

In addition to the affordances and signifiers of any given object, there is also the way humans interact with the object. There are three interaction modes, from the visceral to the behavioral to the reflective, and these follow along cognitive models of fast and slow thinking. Key to designing is understanding how cognition and emotion factor into the way people interact with objects.

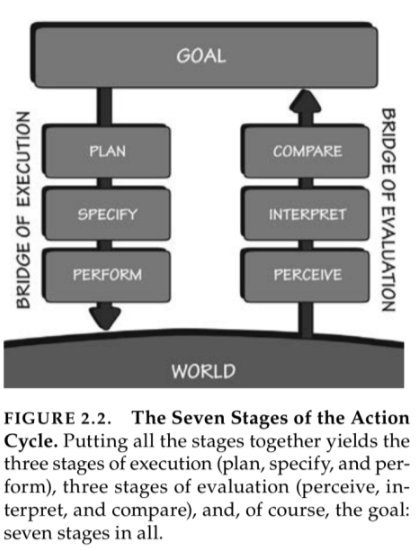

Two Gulfs of Action

- Gulf of Execution - where people try to figure out how it operates

- Gulf of Evaluation - where they try and figure out what happened

Seven Stages of Action

- Goal (form the goal) - What do I want to accomplish?

- Plan (the action) - What are teh alternative action sequences?

- Specify (an action sequence) - What action can I do now?

- Perform (the action sequence) - How do I do it?

- Perceive (the state of the world) - What happened?

- Interpret (the perception) - What does it mean?

- Compare (the outcome with the goal) - Is this okay? Have I accomplished my goal?

For many everyday tasks, goals and intentions are not well specified: they are opportunistic rather than planned. Opportunistic actions are those in which the behavior takes advantage of circumstances. (43)

- people don’t want a quarter-inch drill, they want a quarter-inch hole – but really they want to hang a picture, and they want their house to feel welcoming, or they want to do what others do to make their house welcoming

we like to think we understand ourselves. But the truth is, we don’t. Most of human behavior is a result of subconscious processes. (44)

two types of memory

- declarative memory – for factual information

- procedural memory – recalling activities performed

Three Levels of Processing

a conceptual model not to be taken too literally, but helpful grounding framework for thinking about what a designer needs to think about when designing

-

visceral

- basic protective mechanism of the human affective system

- quick judgments based on environment

- fast and completely subconscious

- great designers use aesthetic sensibilities to drive visceral responses

-

behavioral

- learned skills, triggered by situations that match appropriate patterns

- for designers, most critical aspect is that every action is associated with an expectation

-

reflective

- home of conscious cognition

- where deep understanding develops, where reasoning and conscious decision-making take place

- most important for designer, because memories last far longer than the immediate experience

learned helplessness

- a situation where people experience repeated failures at a task, and they decide the task can’t be done – can be overcome with positive psychology

- we need to remove failure from our vocabulary – every failure is a learning opportunity

human error is usually a result of poor design: it should be called system error. (66)

It is easy to design devices that work well when everything goes as planned. The hard and necessary part of design is to make things work well even when things do not go as planned. (68)

3: Knowledge in the Head and in the World

Chapter Summary

We don’t need the entirety of knowledge of how to precisely use something entirely within our head – it is a combination of knowledge in our head and in the world that we can gather. Memory in the head takes several different forms and serves several different purposes. Understanding how memory works, how short-term and long-term memory differ, and how we can build constraints and cues into the world to overcome shortcomings with memory, is key to successful design.

Knowledge in the Head vs Knowledge in the World

| knowledge in the world | knowledge in the head |

|---|---|

| information is readily and easily available whenever perceivable | marterial in morking memory is readily available. otherwise, considerable search and effort may be required |

| interpretation substitutes for learning. How easy it is to interpret knowledge in the world depends upon the skills of the designer | Requires learning, which can be considerable. Learning is made easier if there is meaning or structure to the material or if there is a good conceptual model |

| Slowed by the need to find and interpret the knowledge. | Can be efficient, especially if so well-learned that it is automated |

| Ease of use at first encounter is high | Ease of use at first encounter is low |

| Can be ugly and inelegant, especially if there is a need to maintain a lot of knowledge. This can lead to clutter. Here is where the skill of the graphics and industrial planner play major roles | Nothing needs to be visible, which gives more freedom to the designer. This leads to cleaner, more pleasing appearance – at the cost of ease of use at first encounter, learning, and remembering. |

The Structure of Memory

- short-term memory

- retains most recent experiences and material

- is fragile

- design implications: 1) don’t count on STM retaining much, 2) use multiple sensory modalities (sight, sound, haptics, hearing, spatial locations, gestures) to deliver different information

- long-term memory

- memory for the past

- not immediately codified, but is through sleep or rehearsal

- design implications: create approximate models/heuristics to aid in retaining info

[The] combination of technology and people that creates super-powerful beings. Technology doesn’t make us smarter. People do not make technology smart. It is the combination of the two, the person plus the artifact, that is smart. (112)

4: Knowing What to Do: Constraints, Discoverability, and Feedback

Chapter Summary

Not all knowledge needs to exist in the head, and there are several ways to convey knowledge in the world, including various flavors of constraints and forcing functions. Additionally, feedback via sound can also guide desired behavior. It is the task of the designer to understand how to leverage these sorts of mechanisms to impart knowledge to the users of their products.

Four Kinds of Constraints

- physical - physical limitations constrain possible operations

- cultural - each culture has a set of allowable actions for social situations that are likely to change with time

- semantic - rely on the meaning of the situation to constrain possible actions

- logical - a relationship between the spatial or functional aspects of a component and the things they control

A usable design starts with careful observations of how the tasks being supported are actually performed, followed by a design process that results in a good fit to the actual ways the tasks get performed. (137)

Forcing Functions

Forcing functions are a form of physical constraint: situations in which the actions are constrained so that failure at one stage prevents the next step from happening. (141)

- interlock - forces operations to take place in a proper sequence, e.g., opening a microwave door and cutting microwave power

- lock-in - keeps an operation active, preventing someone from prematurely stopping it, e.g., jail cells or exit dialogs in word processors or vendor lock-in

- lock-out - prevents someone from entering a space that is dangerous, or prevents an event from occurring, e.g., stairways that have a fire barrier to the basement so people escaping fire don’t go all the way to the basement

- conventions are a special kind of cultural constraint, but often conventions make it hard to adopt new systems – change is hard

- use sound as a signifier when vision isn’t enough, e.g., the backup warning on trucks

- skeuomorphic - the technical term for incorporating old, familiar ideas into new technologies, even though they no longer play a functional role

5: Human Error? No, Bad Design

Chapter Summary

We need design not only for when the system works perfectly, but also for when things do not go to plan. Understanding common error patterns, as well as the mechanisms to counteract them, is key to good design.

[W]hen an error happens, we should determine why, then redesign the product or procedure being followed so that it will never occur again or, if it does, so that it will have minimal impact. (164)

Root Cause Analysis

- investigate the accident until the single underlying cause is found

- most problems don’t have a single underlying cause, and we can’t stop as soon as the first cause is uncovered

- leverage the five whys (came out of Toyota) to get to the real root cause – keep asking why until there are no more answers

- important to resist urge to blame people – most often, the system is to blame

Types of Errors: Slips and Mistakes

Error is defined as deviance from the generally accepted correct or appropriate behavior.

-

slips

- occurs when a person intends to do on action but then ends up doing something else

- action-based slip - a wrong action is performed

- memory-lapse slip - memory fails, so the intended action is not done or results not evaluated

-

mistakes

- occurs when the wrong goal is established or the wrong plan is formed

- rule-based mistake - a person has appropriately diagnosed the situation, but has decided upon an erroneous course of action

- knowledge-based mistake - the problem is misdiagnosed because of erroneous or incomplete knowledge

- memory-lapse mistake - takes place when there is forgetting at the stages of goals, plans, or evaluation

Types of Slips

Capture Slips

- defined as the situation where, instead of the desired activity, a more frequently or recently performed one gets done instead: it captures the activity

- designers need to avoid procedures that have identical opening steps but then diverge

Description-Similarity Slips

- result from performing the correct action on the wrong object

- designers need to ensure that controls and displays for different purposes are significantly different from one another

Memory-Lapse Slips

- common cause of error that can lead to several errors: failure to do all steps, forgetting the outcome of an action

- can be combatted by minimizing amount of steps, or providing vivid reminder of steps that need to be completed

Mode-Error Slips

- occurs when a device has different states in which the same controls have different meanings

- designers must try to avoid modes, but if they are necessary, the equipment must make it obvious which mode is invoked – designers need to compensate for interfering activities

Types of Mistakes

Rule-Based Mistakes

- occurs when

- the situation is mistakenly interpreted, meaning the wrong rule is invoked

- the correct rule is invoked, but the rule itself is faulty

- the correct rule is invoked, but the outcome is incorrectly evaluated

- the design challenge is to present the information about the state of the system in a way that is easy to assimilate and interpret, as well as to provide alternative explanations and interpretations

Knowledge-Based Mistakes

- occurs when people are in novel situations and are consciously problem solving

- best solution is in a good understanding of the system, provided by manuals or intelligent computer systems

Memory-Lapse Mistakes

- occurs when someone forgets the steps or the goal or the plan

-

fixed the same way as memory-lapse slips: make sure all relevant information is continuously available

- you can use checklists (ideally one person to follow, one to check things off) to counteract errors

In the absence of data, it is impossible to make improvements. (192)

- Jidoka - automation with a human touch – systems are mostly automated with a worker who might notice errors and report them

- poka-yoke - “error proofing” or “avoiding errors” – add simple fixtures, jigs, or devices to constrain the operations

Designing for Errors

steps that should be taken:

- understand the causes of error and design to minimize those causes

- do sensibility checks: does the action pass the “common sense” test?

- make it possible to reverse actions – to “undo” them – or make it harder to do what cannot be reversed

- make it easier for people to discover the errors that do occur, and make them easier to correct

- don’t treat the action as an error; rather, try to help the person complete the action properly. think of the action as an approximation to what is desired.

Interruptions and distractions lead to errors, both mistakes and slips. (201)

The best way of mitigating slips is to provide perceptible feedback about the nature of the action being performed, then very perceptible feedback describing the new resulting state, coupled with a mechanism that allows the error to be undone. (207)

The Swiss Cheese Model of Errors

- if each slice represents a condition in the task being done, an accident can happen only if holes in all slices are lined up just right

- well-designed systems are resilient against failure

Design redundancy and layers of defense […] we need to think about systems, about all the interacting factors that lead to human error and then to accidents, and devise ways to make the systems, as a whole, more reliable. (210)

Resilience Engineering

- design systems, procedures, management, and the training of people so they are able to respond to problems as they arise

-

components are being continually assessed, tested, and improved

- put the knowledge required to operate the technology in the world. don’t require that all the knowledge must be in the head. allow for efficient operations hen people have learned all the requirements, when they are experts who can perform without the knowledge in the world, but make it possible for non-experts to use the knowledge in the world. this will also help experts who need to perform a rare, infrequently performed operation or return to the technology after a prolonged absence

- use the power of natural and artificial constrains: physical, logical, semantic, cultural. exploir the power of forcing functions and natural mappings.

- bridge the two gulfs, the gulf of execution and the gulf of evaluation. make things visible, both for execution and evaluation. on the execution side, provide feedforward information: make the options readily available. on the evaluation side, provide feedback: make the results of each action apparent. make it possible to determine the system’s status readily, easily, accurately, and in a form consistent with the person’s goals, plans, and expectations.

6: Design Thinking

Chapter Summary

Defining the modes of interaction for someone using a product are all well and good, but what does the actual act of designing in the real world look like? It is first key to define your problem, first by interrogating it and getting to the real root problem. Then, you apply the same iterative diverge then converge thinking to finding a solution. These processes are best applied iteratively with occasional management gates, and through cross-functional teams. It is expensive and takes a lot of effort to deliver products that meet a real need.

Design Thinking

[I]n design, the secret to success is to understand what the real problem is. (217)

- process is iterative and expansive

- don’t find solution until you understand what real problem is

- apply human-centered design and the double-diamond diverge-converge model of design

- solving the right problem that meets human needs and capabilities

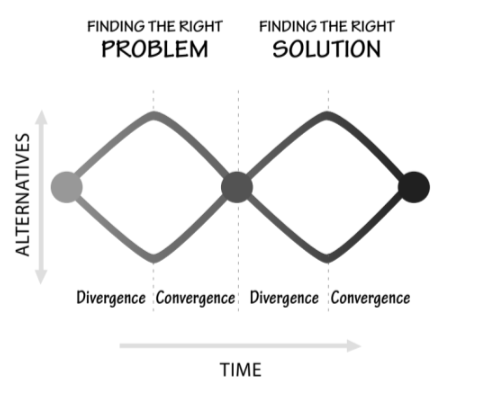

Double-Diamond Model of Design

- two phases, 1) finding the right problem, 2) finding the right solution

- start by questioning the problem given to expand scope, then narrowing down to right problem

- then, expand space of possible solutions before converging on a solution

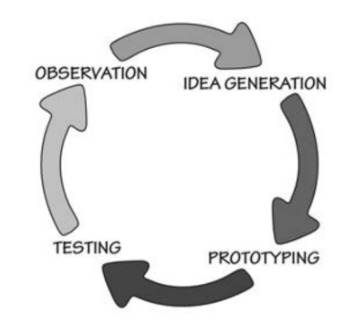

Human-Centered Design Process

-

Observation

- observe would be customers in natural environment, in their normal lives, wherever the product being deigned would be used (applied ethnography)

- no substitute for interacting directly with customer

- marketing and design should work as complementary to each other – they have different concerns

-

Idea Generation

- generate possible solutions

- create numerous ideas, be creative without regards for constraints, and question everything

-

Prototyping

- build quick mock-up of each potential solution

-

Testing

- gather small group that correspond closely to target audience

- ideally 5 – you can test with 5, change the product, test with 5, etc etc. iterate!

- activity-centered design - if the product is being used for many people, you can concentrate on the activities that will be performed, as opposed to a more human-centered design – let the activity define the product and its structure

Tasks and Goals

- task is a small sub-component of a goal

- Carver and Schier suggest three types of goals:

- be-goals – these are foundational, long-lasting, and determine one’s self image

- do-goals – determine the plans and actions to be performed for an activity

- motor-goals – specifies just how the actions are performed

-

design for goals, not tasks

- waterfall method of design – linear, progress in single direction, and once decisions have been made it is difficult to go back

- contrast this with more iterative method, where decisions are deferred, time to experiment

The goal is to have best of both worlds: iterative experimentation to refine the problem and the solution, coupled with management reviews at the gates […] The trick is to delay precise specifications of the product requirements until some iterative testing with rapidly deployed prototypes has been done. (235)

- implicit knowledge - knowledge that only exists in the heads of workers

- Norman’s Law of Product Development - The day a product development process starts, it is behind schedule and above budget.

- inclusive/universal design - designing for people with special needs

[C]omplexity is essential: it is confusion that is undesirable. I distinguished between “complexity”, which we need to match the activities we take part in, and “complicated”, which I defined to mean confusion. (247)

Standardization provides a major breakthrough in usability. (248)

7: Design in the World of Business

Chapter Summary

The previous six chapters are theory, this chapter discusses what the actual market forces that dictate the development of product look like. Leans strongly on two examples: videophones, which were conceived in 1897 but still haven’t been realized, and the typewriter and how it settled on the QWERTY keyboard. The realities of market forces mean that most of your product development takes years, will already be behind schedule, and might build off radical innovation but really represents incremental innovation.

Stigler’s Law - the names of famous people often get attached to ideas even though they had nothing to do with them

Innovation

two types of innovation:

- radical – changes lives and industries, takes years, decades, or even centuries, hard to predict (black swan)

- incremental – makes things better on a small scale, iterative

- we need both types

Design is successful only if the final product is successful – if people buy it, use it, and enjoy it, thus spreading the word. A design that people do not purchase is a failed design, no matter how great the design team might consider it. (293)

Two Key Takeaways

- In order to design good products, we need to think about the ways people interact with those products, through affordances, signifiers, constraints, mappings, feedback, and conceptual models. Signifiers are the most important component of good design because they signal what you can or can’t do with a product, what capabilities a product affords based on who is using that product.

- We need our design to be human-centered, to not assume a happy path, to meet the needs and capabilities of those who use it rather than the other way around. Great design produces pleasurable experiences, experiences that delight, and the key to this is putting the human in the center of your design rather than building in the abstract.

Thoughts

Rating: 9/10 I think over time, this rating might drift up to a 10. This book has lent me a vocabulary to wield in the battle to build usable systems. It is no exaggeration to say that thinking about usability in the way Norman posits has been the difference between success and failure for systems and processes I’ve built. This book is canon for user-centered design and for anyone who designs anything to be used by humans.